To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Hydrostatic equilibriumHydrostatic equilibrium occurs when compression due to gravity is balanced by a pressure gradient which creates a pressure gradient force in the opposite direction. The balance of these two forces is known as the hydrostatic balance. Additional recommended knowledge

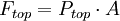

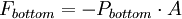

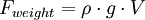

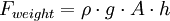

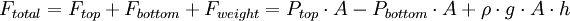

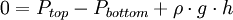

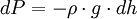

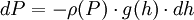

Mathematical considerationFor a volume of a fluid which is not in motion or is in a state of constant motion, Newton's Laws state that it must have zero net force on it - the forces up must equal the forces down. This force balance is called the hydrostatic balance. We can split the gas into a large number of cuboid volume elements. By considering just one element, we can work out what happens to the gas as a whole. There are 3 forces: The force downwards onto the top of the cuboid from the pressure, P, of the fluid above it is, from the definition of pressure, Similarly, the force on the volume element from the pressure of the fluid below pushing upwards is In this equation, the minus sign comes from the directon - this force supports the volume element, rather than pull it down (We are presuming that positive force acts down, however this is irrelevant). Finally, the weight of the volume element causes a force downwards. If the density is ρ, the volume is V and g the standard gravity, then: We can split volume into the area of the top or bottom, times the height. By balancing these forces, the total force on the gas is This is zero if the gas isn't moving. If we divide by A, Or, Ptop-Pbottom is a change in pressure, and h is the height of the volume element - a change in the distance above the ground. By saying these changes are infinitesimally small, the equation can be written in differential form. Density changes with pressure, and gravity changes with height, so the equation would be: ApplicationsFluidsThe hydrostatic equilibrium pertains to hydrostatics and the principles of equilibrium of fluids. A hydrostatic balance is a particular balance for weighing substances in water. Hydrostatic balance allows the discovery of their specific gravities. AstrophysicsHydrostatic equilibrium is the reason stars don't implode, or explode. In astrophysics, in any given layer of a star, there is a balance between the thermal pressure (outward) and the weight of the material above pressing downward (inward). This balance is called hydrostatic equilibrium. A star is like a balloon. In a balloon, the gas inside the balloon pushes outward and the Earth's atmospheric pressure plus the elastic material supply just enough inward compression to balance the gas pressure. In the case of a star, the star's internal gravity supplies the inward compression. The isotropic gravitational field compresses the star into the most compact shape possible: a sphere. Note however that a star becomes a sphere only in the ideal case where only its own self-gravity is involved. In real situations there are other forces at play that alter the outcome, most notably centrifugal force from a star's rotation. A rotating star becomes an oblate spheroid when in hydrostatic equilibrium. An extreme example of this is the star Vega, which has a rotation period of 12.5 hours and is about 20% fatter at the equator than at the poles because of it. If the star has a massive nearby companion object then tidal forces come into play as well, further distorting the star into an ellipsoidal shape. For an example of this see Beta Lyrae. The concept of hydrostatic equilibrium has also become important in determining whether an astronomical object is a planet, dwarf planet, or small solar system body. According to the definition of planet adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 2006, planets and dwarf planets are objects that have sufficient gravity to overcome their own rigidity and assume hydrostatic equilibrium. Since the terrestrial planets and dwarf planets (likewise the largest satellites like the Moon and Io) have rough surfaces and so are not perfectly in equilibrium this definition evidently has some flexibility, but as of yet a specific means of quantifying an object's shape by this standard has not been announced. It is also important for the intracluster medium, where it restricts the amount of gas that can be present in the core of a cluster of galaxies. AtmosphericsHydrostatic equilibrium can explain why the Earth's atmosphere does not collapse to a very thin layer on the ground. In the atmosphere, the pressure of air decreases with increasing altitude. This causes an upward force, called the pressure gradient force, which tries to smooth over pressure differences. The force of gravity, on the other hand, almost exactly balances this out, keeping the atmosphere bound to the earth and maintaining pressure differences with altitude. Without the pressure gradient force, the atmosphere would collapse to a much thinner shell around the earth, and without the force of gravity, the pressure gradient force would diffuse the atmosphere into space, leaving Earth with hardly any atmosphere. See also

References

Categories: Fluid mechanics | Hydrostatics |

|

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Hydrostatic_equilibrium". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. |