Molecular motors: Power much less than expected?

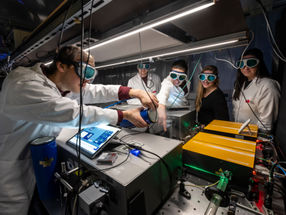

An innovative measurement method was used at the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw for estimating power generated by motors of single molecule in size, comprising a few dozens of atoms only. The findings of the study are of crucial importance for construction of future nanometer machines – and they do not instil optimism.

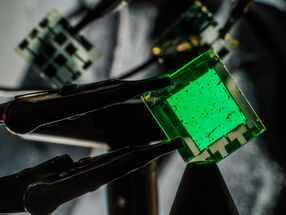

Researchers at the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw have measured power generated by molecular machines -- collectively rotating molecules of liquid crystals in a monomolecular layer on the surface of water.

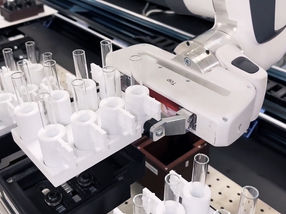

IPC PAS, Grzegorz Krzyżewski

Nanomachines are devices of the future. Composed of a very little number of atoms, they would be in the range of billionth parts of a meter in size. Construction of efficient nanomachines would lead most likely to another civilization revolution. That's why researchers around the world look at various molecules trying to put them at mechanical work.

Researchers from the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IPC PAS) in Warsaw were among the first to have measured the efficiencies of molecular machines composed of a few dozen of atoms. "Everything points to the belief that the power of motors composed of single, relatively small molecules is considerably less than expected", says Dr Andrzej Żywociński from the IPC PAS, one of the co-authors of the paper published in the "Nanoscale" journal.

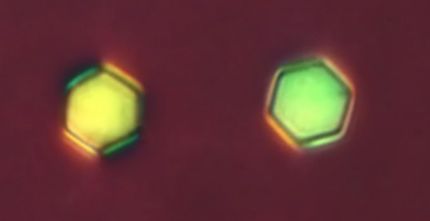

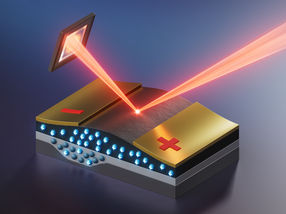

Molecular motors studied at the IPC PAS are molecules of smectic C*-type liquid crystals, composed of a few tens of atoms (each molecule is 2.8 nanometer long). After depositing on the surface of water, the molecules, under appropriate conditions, form spontaneously the thinnest layer possible – a monomolecular layer of specific structure and properties. Each liquid crystal molecule is composed of a chain with its hydrophilic terminal anchored on the surface of water. A relatively long, tilted hydrophobic part protrudes over the surface. So, monomolecular layer resembles a forest with trees growing at certain angle. The free terminal of each chain includes two crosswise arranged groups of atoms with different sizes, forming a two-blade propeller with blades of different lengths. When evaporating water molecules strike the "propellers", the entire chain starts to rotate around its "anchor" due to asymmetry.

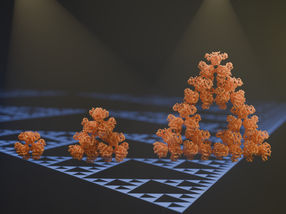

Specific properties of liquid crystals and the conditions of experiment give rise to an in-phase motion of adjacent molecules in the monolayer. It is estimated that "tracts of the forest" of up to one trillion (10^12) molecules, forming areas of millimeter sizes on the surface of water, are able to synchronise their rotations. "Moreover, the molecules we studied were rotating very slowly. One rotation could be as long as a few seconds up to a few minutes. This is a much desired property. Would the molecules be rotating with, for instance, megahertz frequencies, their energy could be hardly transferred on larger objects", explains Dr Żywociński.

Earlier power estimations for molecular nanomotors were related either to much larger molecules, or to motors powered by chemical reactions. In addition, these estimations did not account for the resistance of the medium where the molecules worked.

Free, collective rotations of liquid crystal molecules on the surface of water can be easily observed and measured. Researchers from the IPC PAS checked how the speed of rotation changes as a function of temperature; they estimated also changes in (rotational) viscosity in the system under study. It turned out that the energy of single molecule motion generated during one rotation is very low: just 3.5•10^-28 joule. This value is as many as ten million times lower than the thermal motion energy.

"Our measurements are a bucket of cold water for designers of molecular nanomachines", notices Prof. Robert Hołyst (IPC PAS).

In spite of generating low power, rotating liquid crystal molecules can find practical applications. This is due to the fact that a large ensemble of collectively rotating molecules generates a correspondingly higher power. Moreover, a single square centimeter of the surface of water can accommodate many such ensembles with trillions of molecules each.

The same research at the IPC PAS included also a comparison of power generated by rotating molecules of liquid crystals with the power of a single biological motor – a very large molecule known as adenosinetriphosphatase (ATPase). The enzyme plays a role of sodium-potassium pump in animal cells. With appropriate calculations it was estimated that the density of energy generated in a volume unit was about 100,000 times higher for ATPase than for rotating liquid crystals.

"It took millions of years for evolution to develop such an efficient molecular pump. We, humans, have been working with molecular machines for a couple or maybe a dozen of years only", comments Prof. Hołyst and adds: "Give us just a bit of time".