To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

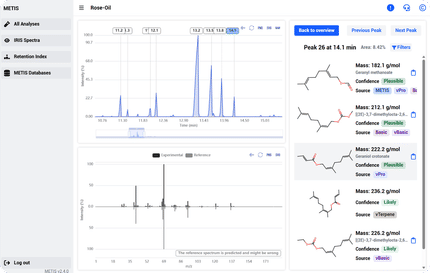

JadeJade is an ornamental stone. The term jade is applied to two different rocks that are made up of different silicate minerals. Nephrite jade consists of the calcium- and magnesium-rich amphibole mineral actinolite (aggregates of which also make up one form of asbestos). The rock called jadeitite consists almost entirely of jadeite, a sodium- and aluminium-rich pyroxene. The trade name Jadite [sic] is sometimes applied to translucent/opaque green glass. The English word 'jade' is derived from the Spanish term piedra de ijada (first recorded in 1565) or 'loin stone', from its reputed efficacy in curing ailments of the loins and kidneys. 'Nephrite' is derived from lapis nephriticus, the Latin version of the Spanish piedra de ijada.[1] Nephrite and jadeite were used by people from the prehistoric for similar purposes. Both are about the same hardness as quartz, and they are exceptionally tough. They are beautifully coloured and can be delicately shaped. Thus it was not until the 19th century that a French mineralogist determined that "jade" was in fact two different materials. Among the earliest known jade artifacts excavated from prehistoric sites are simple ornaments with bead, button, and tubular shapes[2]. Additionally, jade was used for axe heads, knives, and other weapons. As metal-working technologies became available, the beauty of jade made it valuable for ornaments and decorative objects. Jade has a Mohs hardness of between 6.5 and 7.0,[3] so it can be worked with quartz or garnet sand, and polished with bamboo or even ground jade. Nephrite can be found in a creamy white form (known in China as "mutton fat" jade) as well as in a variety of green colours, whereas jadeitite shows more colour variations, including dazzling blue, lavender-mauve, pink, and emerald-green colours. Of the two, jadeite is rarer, documented in fewer than 12 places worldwide. Translucent emerald-green jadeitite is the most prized variety, both now and historically. As "quetzal" jade, bright green jadeitite from Guatemala was treasured by Mesoamerican cultures, and as "kingfisher" jade, vivid green rocks from Burma became the preferred stone of post-1800 Chinese imperial scholars and rulers. Burma (Myanmar) and Guatemala are the principal sources of modern gem jadeitite, and Canada of modern lapidary nephrite. Nephrite jade was used mostly in pre-1800 China as well as in New Zealand, the Pacific Coast and Atlantic Coasts of North America, Neolithic Europe, and south-east Asia. In addition to Mesoamerica, jadeitite was used by Neolithic Japanese and European cultures. Jade is the official gemstone of British Columbia, where it is found in large deposits in the Lillooet and Cassiar regions. It is also the official gemstone of the state of Alaska, found particularly in the Kobuk area. A two ton block of jade sits outside the Anchorage Visitor’s Center in downtown Anchorage, Alaska, mined from near Kobuk and donated to the city as a showpiece. Product highlight

HistoryPrehistoric and Historic ChinaDuring Neolithic times, the key known sources of nephrite jade in China for utilitarian and ceremonial jade items were the now depleted deposits in the Ningshao area in the Yangtze River Delta (Liangzhu culture 3400–2250 BC) and in an area of the Liaoning province in Inner Mongolia (Hongshan culture 4700–2200 BC)[4]. Jade was used to create many utilitarian and ceremonial objects, ranging from indoor decorative items to jade burial suits. Jade was considered the "imperial gem". From about the earliest Chinese dynasties until present, the jade deposits in most use were not only from the region of Khotan in the Western Chinese province of Xinjiang but also from other parts of China, like Lantian, Shaanxi. There, white and greenish nephrite jade is found in small quarries and as pebbles and boulders in the rivers flowing from the Kuen-Lun mountain range northward into the Takla-Makan desert area. River jade collection was concentrated in the Yarkand, the White Jade (Yurungkash) and Black Jade (Karakash) Rivers. From the Kingdom of Khotan, on the southern leg of the Silk Road, yearly tribute payments consisting of the most precious white jade were made to the Chinese Imperial court and there transformed into objets d'art by skilled artisans as jade was considered more valuable than gold or silver. Jade became a favorite material for the crafting of Chinese scholars objects, such as rests for calligraphy brushes, as well as the mouthpieces of some opium pipes, due to the belief that breathing through jade would bestow longevity upon smokers who used such a pipe.[5] Jadeite, with its bright emerald-green, pink, lavender, orange and brown colours was imported from Burma to China only after about 1800. The vivid green variety became known as Feicui (翡翠) or Kingfisher (feathers) Jade. It quickly replaced nephrite as the imperial variety of jade. In the long history of the art and culture of the enormous Chinese empire, jade has always had a very special significance, roughly comparable with that of gold and diamonds in the West. Jade was used not only for the finest objects and cult figures, but also in grave furnishings for high-ranking members of the imperial family. Today, too, this gem is regarded as a symbol of the good, the beautiful and the precious. It embodies the Confucian virtues of wisdom, justice, compassion, modesty and courage, yet it also symbolises female-eroticism. Prehistoric and Early Historic KoreaThe use of jade and other greenstone was a long-term tradition in Korea (c. 850 B.C. - A.D. 668). Jade is found in small numbers of pit-houses and burials. The craft production of small comma-shaped and tubular 'jades' using materials such as jade, microcline, jasper, etc in southern Korea originates from the Middle Mumun Pottery Period (c. 850-550 B.C.)[6]. Comma-shaped jades are found on some of the gold crowns of Silla royalty (c. A.D. 300/400-668) and sumptuous elite burials of the Korean Three Kingdoms. After the state of Silla united the Korean Peninsula in A.D. 668, the widespread popularisation of death rituals related to Buddhism resulted in the decline of the use of jade in burials as prestige mortuary goods.. MāoriNephrite jade in New Zealand is known as pounamu in the Māori language, and is highly valued, playing an important role in Māori culture. It is considered a taonga, or treasure, and therefore protected under the Treaty of Waitangi, and the exploitation of it is restricted and closely monitored. The South Island of New Zealand is Te Wai Pounamu in Māori - "The [land of] Greenstone Water" - because greenstone used to be easily obtainable in rivers. An alternative (and more probable) Maori place-name for the South Island is Te Wahi Pounamu -"The Place of Greenstone". Weapons and ornaments were made of it; in particular the 'mere' (short club), and the Hei-tiki (neck pendant). These were believed to have their own mana, handed down as valuable heirlooms, and often given as gifts to seal important agreements. With no metal tools, it was also used for a range of tools such as adzes. In New Zealand English the normal term is "greenstone" and jewellery of it in Māori designs is widely popular with locals of all races, and with tourists - although much of the jade itself is now imported from British Columbia and elsewhere. MesoamericaJade was a rare and valued material in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The only source from which the various indigenous cultures, such as the Olmec and Maya, for example, could obtain jade was located in the Motagua River valley in Guatemala. Jade was largely an elite good, and was usually carved in a variety ways, whether serving as a medium upon which hieroglyphs were inscribed, or shaped into symbolic figurines. Generally, the material was highly symbolic, and it was often employed in the performance of ideological practices and rituals. Today, Guatemala produces jadeite in a variety of colours, ranging from soft translucent lilac, blue, green, yellow, and black. It is also the source of new colours, including "rainbow jade" and the unique "Galactic Gold," a black jadeite with natural incrustations of gold, silver and platinum.[7] Other namesBesides the terms already mentioned, jadeite and nephrite are sometimes referred to by the following: JadeiteAgate verdâtre, Feitsui, Jadeit, Jadeita, Natronjadeit, Yunnan Jade, Yu-stone, Sinkiang jade. NephriteAotea, Axe-stone, B.C. Jade, Beilstein, British Columbian Jade, Canadian Jade, Grave Jade, Kidney Stone, Lapis Nephriticus, Nephrit, Nephrita, Nephrite (of Werner), New Zealand Greenstone, New Zealand Jade, Siberian Jade, Spinach Jade, Talcum Nephriticus, Tomb Jade. Faux JadeMany minerals are sold as jade. Some of these are: serpentine (also bowenite), carnelian, aventurine quartz, glass, grossularite, Vesuvianite, soapstone (and other steatites such as shoushan stone) and recently, Australian chrysoprase. "Korean jade," "Suzhou jade," "Styrian jade," "Olive jade", and "New jade" are all really serpentine; "Transvaal jade" or "African jade" is grossularite; "Peace jade" is a mixture of serpentine, stichtite, and quartz; "Malaysia jade" is dyed quartz; "Mountain jade" is dyed dolomite marble. In almost all dictionaries, the Chinese character 'yù' (玉) is translated into English as 'jade'. However, this frequently leads to misunderstanding: Chinese, Koreans, and Westerners alike generally fail to appreciate that the cultural concept of 'jade' is considerably broader in China and Korea than in the West. A more accurate translation for this character on its own would be 'precious/ornamental rock'. It is seldom, if ever, used on its own to denote 'true' jade in Mandarin Chinese; for example, one would normally refer to 'ying yu' (硬玉, 'hard jade') for jadeite, or 'ruan yu' (軟玉, 'soft jade') for nephrite. The Chinese names for many ornamental non-jade rocks also incorporate the character 'yù', and it is widely understood by native speakers that such stones are not, in fact, true precious nephrite or jadeite. Even so, for commercial reasons, the names of such stones may well still be translated into English as 'jade', and this practice continues to confuse the unwary. EnhancementJade may be enhanced (sometimes called "stabilized"). There are three main methods, sometimes referred to as the ABC Treatment System:

Gallery of Chinese jadesSee also

References

Further reading

Categories: Silicate minerals | Gemstones |

|

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Jade". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. |