To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine), most commonly known today by the street name ecstasy (often abbreviated to E, X, or XTC), is a semisynthetic empathogen-entactogen of the phenethylamine family. It has greater stimulant effects and fewer visual effects than other common "trip" producing drugs. It is considered mainly a recreational drug, though is often used as an entheogen and as a tool to supplement various practices for transcendence, including in meditation, psychonautics, and illegal psychedelic psychotherapy, whether self-administered or not. MDMA is illegal in most countries, and its possession, manufacture or sale may result in criminal prosecution. Product highlight

HistoryMDMA is often rumored to have been first synthesized by the famous German chemist Fritz Haber in 1891; however, this is incorrect.[2] The patent for MDMA—referred to as methylsafrylamin—which is not under dispute, was originally filed on December 24 1912 by the German pharmaceutical company Merck, after being first synthesised for them by German chemist Anton Köllisch at Darmstadt earlier that year.[3][4] The patent was granted in 1914; Köllisch died in 1916 unaware of the impact his synthesis would have. At the time, MDMA was not known to be a drug in its own right; rather, it was patented as an intermediate chemical used in the synthesis of a hydrastinine (a drug intended to control bleeding from wounds) analogs[citation needed]. During 1927, Max Oberlin used MDMA as a mimic for adrenaline as the compound has a similar chemical structure. At this time the first animal studies were performed to demonstrate the effects of MDMA on blood glucose levels and vascular tissue.[3] This study was discontinued due to the high costs of the chemical synthesis. Interest was revived in the compound as a possible human stimulant by Wolfgang Fruhstorfer in 1959, although it is unclear if tests were actually performed on humans. The synthesis of the compound first appeared in 1960.[5] The U.S. Army did, however, carry out lethal dose studies of MDMA and several other compounds on animals in the mid-1950s. It was given the name EA-1475, with the EA standing for either (accounts vary) "Experimental Agent" or "Edgewood Arsenal."[6] The results of these studies were not declassified until 1969. MDMA appeared sporadically as a street drug in the late 1960s (when it was known as the "love drug"). MDMA began to be used therapeutically in the mid-1970s after the chemist Alexander Shulgin introduced it to psychotherapist Leo Zeff. As Zeff and others spread word about MDMA, it developed a reputation for enhancing communication, reducing psychological defenses, and increasing capacity for introspection. However, no formal measures of these putative effects were made and blinded or placebo-controlled trials were not conducted. A small number of therapists—including George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfson—used it in their practices until it was made illegal. Due to the wording of the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, MDMA was automatically classified as a Class A drug in 1977 in the UK. In the early 1980s, MDMA rose to prominence in certain trendy nightclubs in the Dallas area, then in gay dance clubs.[7] From there use spread to rave clubs, and then to mainstream society. The street name of "ecstasy" was coined in California in 1984.[citation needed] The drug was first proposed for scheduling by the DEA in July 1984,[5] and was classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the United States from May 31, 1985.[8] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, ecstasy was widely used in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, becoming an integral element of rave culture and other psychedelic/dancefloor-influenced music scenes, such as Madchester and Acid House. Spreading along with rave culture, illegal MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later in high schools. It rapidly became one of the four most widely used illegal drugs in the U.S., along with cocaine, heroin and cannabis.[citations needed] Effects

Mode of actionMDMA's effects are due primarily to the drug's higher affinity for SERTs than serotonin itself. SERTs are the part of the serotonergic neuron which removes serotonin from the synapse to be recycled or stored for later use. Not only does MDMA inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, but it actually reverses the action of the transporter so that it actually begins pumping serotonin into the synapse from inside the cell.[9] This usually causes the serotonin storage vesicles to be emptied after only a few hours with a standard recreational dose, and may result in a permanent deformation of the transporters[citation needed]. In addition, MDMA has a partial affinity for blocking the reuptake of dopamine and a smaller affinity still for blocking that of norepinephrine as well as other neurotransmitters in smaller quantities. The former two neurotransmitters, amongst others which may also be released in small amounts, are responsible for increased energy and contribute to the "speedy" feeling of the drug experience, whereas serotonin contributes primarily to feelings of well-being, euphoria, and decreased hostility. The empathic action of MDMA is yet to be well understood, but one theory is that oxytocin, a hormone and neurotransmitter crucial to social bonding, is released in large quantities when MDMA is taken.[10] Subjective effectsThe primary effects of MDMA include an increased awareness of the senses, feelings of openness, euphoria, empathy, love, happiness, heightened self-awareness, feeling of mental clarity and an increased appreciation of music and movement. Some users depending on the purity and kind of the pill, will feel lighter and stronger and will be able to do things that they cannot do sober. Examples are increased athletic ability and being able to do heavy lifting. Tactile sensations are enhanced for some users, making physical contact with others more pleasurable.[11] Other side effects, such as jaw clenching and elevated pulse, are common. Some users report effects similar to those of softer stimulants such as caffeine, and a few report effects comparable to harder stimulants such as cocaine. Alexander Shulgin stated that the single best use of MDMA was to facilitate more direct communication between people involved in significant emotional relationships.[citation needed] Psychiatrist George Greer came to the same conclusion in his report on the first 29 subjects administered MDMA in his practice, with the MDMA having been synthesized in Shulgin's lab.[12] Recreational use

MDMA use has increased markedly since the late 1980s, and spread beyond its original subcultures to mainstream use, with prices generally falling, although there is still wide geographical variance, both regionally and between countries. United KingdomIn 1995 it reported that the street price per pill was, "about £15 each,"[13] although two years later this had shifted to a range of £8 to £15 each."[14] A 2001 Home Office study reported that the cost per pill to end-point consumer, "could be as little as £7.50, or as much as £10 to £15 when purchased in clubs."[15] In 2007 the Greater London Authority highlighted regional variations, reporting[16] that the average street price per pill in five selected cities was:

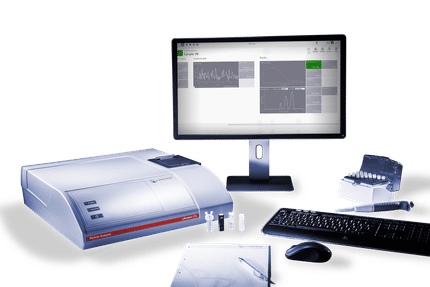

SupplyWorldwide, almost all MDMA is supplied via clandestine routes. The synthesis of MDMA is more complex than that of analogues such as methamphetamine, but still well within the grasp of a university-level chemistry student. Arguably the most difficult part of the synthesis is obtaining the necessary chemical precursors: some have few legitimate uses outside of clandestine drug production, and purchases of them are often illegal or heavily monitored by government agencies like the DEA. PurityBecause of its illegality in most countries, the typical recreational user is unable to verify the purity of a substance sold as MDMA without testing or researching on the Internet. Some MDMA pills have been found to contain various substances; typical substances include caffeine, methamphetamine and ephedrine, all of which have stimulant effects. Scientific surveys of seized Ecstasy pills indicate that purity levels are generally high, and that adulterants are rare.[17] In sharp contrast to this information, current (as of 11/16/07) EcstasyData.org stats indicate that on average over the past 11 years, only 37.4% of pills tested contained MDMA alone as an active ingredient, and 44.2% of pills tested contained no MDMA at all, with the remaining 18.4% containing MDMA in addition to adulterants.[2] A full and proper characterization of ecstasy pills requires advanced lab techniques, such as high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (usually referred to as HPLC-MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (usually referred to as GC-MS) and gas chromatography-infrared spectroscopy (usually referred to as GC-IRD). Ecstasydata.org, a non-profit organization, uses such techniques to analyze MDMA pills for a fee. It is also possible to use a less accurate presumptive alkaloid test known as the Marquis reagent. DanceSafe, among other companies, provides home testing kits to verify the contents of MDMA pills. PillReports.com and Trancesafe.com each provide the results of home testing kits in addition to the suspected contents when a test has not been performed. Ecstasy pillsPills come in a variety of "brands", usually identified by the icons stamped on the pills. Many popular icons are appropriated for this use; an example would be "Red Mercedes", which gets its name because of its red color and Mercedes-Benz logo imprinted on it. However the brands do not consistently designate the actual active compound within the pill, as it is possible for "copycat" manufacturers to make their own pills which replicate the features of a well-known brand. MDMA powder/crystals

MDMA powder, usually the hydrochloride, is often simply called 'crystal' or 'molly', and 'mandy', and in the UK 'Muds', 'Mud' or 'madman' (a play on words- MaDMAn), a mutation of 'madman' 'mandy', and 'MD'. This powder is produced in MDMA labs and provided to the pill-manufacturers to press the tablets at a different place. In many parts of the world the usage of plain MDMA powder instead of pills is popular. One of the reasons for this might be the control over dosage and purity. MDMA is very rarely cut, for its taste is so strong, distinctive and (many would argue) unpleasant that it would be very easy for a user to tell if it were impure. Dealers are more likely to simply sell an amount that is smaller than they claim. When pressed into pill tablets, MDMA powder is always mixed with pill binders because pure MDMA cannot be pressed. Powder or crystal MDMA can be snorted, which makes the effect begin and end quicker. Some users claim that snorting it results in a more intense effect. Snorting however is painful compared to drugs such as cocaine and ketamine, and many users prefer oral administration either by applying a 'dab' to the tongue and washing it down with water, or mixing it into a drink. Some people also 'bomb' pure MDMA, whereby a dose is wrapped in cigarette papers (e.g. Rizla) and then swallowed. This is the preferred method of ingestion for many users as the taste is quite unpleasant and can be exacerbated by the heightened sense of taste which can be a feature of MDMA use. Use in psychotherapySome scientists have suggested that MDMA may facilitate self-examination with reduced fear, which may prove useful in some therapeutic settings. In 1980, psychiatrist George Greer synthesized MDMA in the lab of Alexander Shulgin, then administered it to about 80 of his clients over the next five years, until MDMA was scheduled in 1985. In a published summary of the effects,[18] subjects reported improvements in various, mild psychiatric disorders and other personal benefits, especially improved intimate communication with their significant others. In a subsequent publication on the treatment method, one patient with severe pain from terminal cancer reported definitive and lasting pain relief and improved quality of life.[19] In 2001, the FDA granted permission for experimental administration of MDMA to patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. This research is being sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).[20] First of those studies was conducted by Jose Carlos Bouso, a Spanish therapist who used the MDMA with women that had been raped, but he only could finish the first part of the study for political reasons, and it has yet to be completed. A parallel similar study is currently underway in Switzerland which should finish in 2008.[21] This research in patients builds on studies in which MDMA was given to healthy volunteers. The first of these healthy volunteer studies was conducted by Dr. Charles Grob, with other studies done by Dr. Franz Vollenweider in Switzerland, Drs. John Mendelson and Reese Jones at the University of California San Francisco, and Drs. Magi Faree and Rafael de la Torre in Spain. It has been proposed that MDMA should be considered the prototypical member of a novel category of drug, called "empathogen" and/or "entactogen."[22][23] SynthesisSafrole, a colorless or slightly yellow oil, extracted from the root-bark or the fruit of sassafras plants is the primary precursor for all manufacture of MDMA. There are numerous synthetic methods available in the literature to convert safrole into MDMA via different intermediates. One common route is via the MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone, also known as piperonyl acetone) intermediate. This intermediate can be produced in at least two different ways. One method is to isomerize safrole in the presence of a strong base to isosafrole and then oxidize isosafrole to MDP2P. Another, reportedly better method, is to make use of the Wacker process to oxidize safrole directly to the MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxy phenyl-2-propanone) intermediate. This can be done with a palladium catalyst. Once the MDP2P intermediate has been produced it is then consumed via a reductive amination to form MDMA as the product. According to DEA Microgram newsletters very little safrole is actually required to make MDMA.[24] "Ocotea cymbarum is an essential oil... that typically contains between 80 and 94 percent safrole," "a 500-milliliter bottle of Ocotea cymbarum sells for $20 to more than $100," "An MDMA producer with access to the proper chemicals can use a 500-milliliter quantity of Ocotea cymbarum to produce an estimated 1,300 to 2,800 tablets containing 120 milligrams of MDMA." Legal issuesUse, supply and trafficking of ecstasy are currently illegal in most countries. Ecstasy is illegal in all countries belonging to the United Nations. In the United States, MDMA was legal and unregulated until May 31, 1985, at which time it was added to DEA Schedule I, for drugs deemed to have no medical uses and a high potential for abuse. During DEA hearings to criminalize MDMA, most experts recommended DEA Schedule III prescription status for the drug, due to its beneficial usage in psychotherapy. The judge overseeing the hearings, Francis Young, also made this recommendation. Nonetheless, the DEA classified it as Schedule I.[25] That same year, the World Health Organization's Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule I of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Unlike the Controlled Substances Act, the Convention has a provision in Article 7(a) that allows use of Schedule I drugs for "scientific and very limited medical purposes." The committee's report stated:[26]

In the United Kingdom, MDMA is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, making it illegal to sell, buy, or possess without a license. Penalties include a maximum of seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or unlimited fine for production or trafficking. A mandatory seven year sentence is now the penalty for a third conviction for trafficking. Health concernsWhile the short term side effects and contraindications of MDMA are fairly well known, there is significant debate within the scientific and medical community over the long term effects and the possibility for physical harm arising from excessive and irresponsible MDMA use. Government studiesThe chief executive of the UK Medical Research Council stated MDMA was "on the bottom of the scale of harm," and the Science & Technology Committee rated it of lower concern than for alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis, when examining the harmfulness of any given drug. The UK study placed great weight on the risk for acute physical harm, the propensity for physical and psychological dependency on the drug, and the negative familial and societal impacts of the drug. On these factors, the study places MDMA relatively low, which reflects its lower score in comparison to the risks of alcohol.[27][28] PhysicalThe short-term health risks of taking MDMA include hypertension, dehydration and hyperthermia. In the raving subculture, use of MDMA can increase the risks of dehydration and hyperthermia, as the drug's stimulatory effects can mask the body's normal sense of exhaustion and thirst. The risk of hyperthermia may be increased by a high fat diet, and the mechanism the activation of uncoupling protein (UCP) in mitochondria.[29][clarify] MDMA affects the regulation of the body's internal systems. Continuous dancing without sufficient breaks or drinks can lead to dangerous overheating and dehydration, and serves to significantly enhance the drug's neurotoxic action. Drinking too much water without adequate salt can cause hyponatremia or water intoxication, although this is less common than overheating. Hypertension is a risk in some users due to the increase in heart rate and blood pressure. This risk increases as dose increases. [30] Neurological overviewTo begin, it has been established that MDMA affects the brains of humans and lower primates differently, especially in terms of long-term changes. In both animals, MDMA causes a reduction in the concentration of serotonin transporters (SERTs) in the brain. Baboons who were given a neurotoxic dose of MDMA only showed partial regrowth of SERTs when scanned a year later.[31] In contrast, human studies differ in that those who had never used ecstasy were indistinguishable in PET brain scan studies from former ecstasy users. However, the same study also concluded that the reduction in memory performance due to heavy, prolonged MDMA use may be long-lasting.[32] Although oxidative stress (see neurotoxicty theory below) may cause SERTs to degrade faster than they are able to be replaced, the serotonin axon itself seems to have been spared, which indicates that neurotoxicity may not be the means by which SERT count was reduced. It is possible that excess serotonin in the synapse due to MDMA, especially if uses occur within a short period, causes the serotonin cells to produce fewer SERTs, a phenomenon which has already been demonstrated with other serotonin-depleting drugs.[33] MDMA use may also cause a decrease in the number of serotonin receptors on the dendrite of the neuron. (See down-regulation theory below.) For a detailed and comprehensive explanation of this topic, see TheDea.org's evaluation of studies.[34] Receptor down-regulationOne theory of SERT-depletion arising out of long-term MDMA use is receptor down-regulation which is one form of synaptic plasticity. When any neurotransmitter is present in excess for prolonged periods of time, the brain responds in an attempt to reestablish its own natural neuro-electrical balance. Weekly use of MDMA over a prolonged period may actually cause serotonin receptors to retreat into the dendrite of serotonin nerve cells,[35] in addition to enticing serotonin cells lower its own SERT count.[clarify] The change in synaptic serotonin concentration due to recreational MDMA use is at the extreme end of what is even possible in the brain and therefore, down-regulation could occur fairly easily with regular use.[citation needed] This process causes the brain to become desensitized to the neurotransmitters present in the synapses and therefore also to the effects of MDMA itself. Therefore, in addition to a generally decreased quality of mood between doses, greater amounts of MDMA are required to achieve the same level of desired effects. It is this cycle that is often believed to be the cause of long-term emotional problems among regular ecstasy users.[citation needed] NeurotoxicityUnder another theory, MDMA is considered neurotoxic in humans. While the method of this toxicity has not been definitively established, the current leading theory is that the metabolism of MDMA-induced dopamine release leads to the lipid peroxidation of serotonergic neurons. This occurs when MAO-B breaks up dopamine into free radicals capable of damaging cells, leading to a reduction in SERT count and possibly damage or destruction of the axon itself, thus interfering with the integrity of the brain's serotonin network.[36][37] Normally, the brain is able to protect itself from oxidative stress, but it is believed that the aforementioned damage can be attributed to MDMA's unique interaction with serotonin transporters. Not only does MDMA reverse the normal functioning of the transporter in which case serotonin is pumped out of the cell, but once the stored serotonin has been depleted, the transporter begins to take up dopamine which has been shown to be toxic to serotonin cells by itself. Once MAO oxidizes dopamine inside the serotonin cell, the damage is greatly magnified. Several studies have demonstrated that such damage in the brain is reversible after prolonged abstinence from the drug.[38][39] In severe cases, however, the possibility for recovery of cognitive functions may be much more limited.[40] Neurotoxicity of serotonergic neurons would occur in selective areas of the human brain as serotonin cells are highly concentrated in certain areas such as the neocortex and hippocampus. Although some studies have demonstrated this, the rate at which this damage occurs is disputed. U.S. government-funded studies [41] performed by George Ricaurte at Johns Hopkins University, which have demonstrated catastrophic brain damage occurring due to MDMA exposure, have been widely discredited by the scientific community.[42][43] The second study on the subject, which claimed that a single recreational dose of MDMA could cause Parkinson's Disease in later life, was actually retracted by Ricaurte himself after he discovered his lab had administered methamphetamine, a known neurotoxin, and not MDMA.[44] Antioxidants have been shown to prevent the neurotoxicity of MDMA in rats. In one study, intravenous administration of alpha lipoic acid completely blocked the neurotoxic effects of MDMA. No scientific experiment has been performed to date with human subjects, although some users report that taking various combinations of antioxidants before, during, and after using MDMA serves to moderate the subsequent mood-dip and improve recovery time.[45] The administration of an SSRI in rats prior to the administration of MDMA has been shown to completely block neurotoxicity. This is due to the binding of such medications with SERTs. However, administering an SSRI prior to administration of MDMA also completely or partially blocks the desired effects of the latter, something a large number of users prescribed an SSRI have reported. As a compromise it has been shown that administration of an SSRI 3-4 hours after MDMA, at which time the primary effects will have tapered off significantly, markedly limits neurotoxicity overall despite some axonal damage having already occurred.[46] Once again, no such scientific experiment has been performed on human test subjects, and potential complications may still exist.[citation needed] It should also be noted that the production and introduction into the active brain of serotonin is a much lengthier process than is that of dopamine.[47] Therefore, users who redose once the serotonergically-induced effects of MDMA have mostly diminished are likely not stimulating the release of serotonin at all as a single recreational dose of MDMA is likely to have depleted these rather limited reserves. The subsequent effects of redosing are therefore due almost entirely to the action of increased dopamine in the brain, and therefore, once again, neurotoxicity is significantly enhanced. PsychologicalMDMA use commonly results in a rebound period of poor mood or possibly depression commonly known as a "comedown", the length and severity of which depends on the user, the dose and the total duration of MDMA's activity in the body. Heavy or frequent use may precipitate lasting depression and anxiety in vulnerable users, particularly those prone to depression or other mental disorders as well as anyone in a state of crisis in their life. "Redosing" in an attempt to extend MDMA's desired effects has been shown to substantially increase neurotoxicity as well as the undesired physical side effects associated with MDMA use such as trisma and bruxia, which are caused by MDMA's partial dopaminergic affinity. The longer MDMA is active and being metabolized in the brain, the greater the neurotoxic damage and the greater the risk of short-term emotional problems. The more occasions MDMA is used, the greater the chances of long-term problems.[48] Deficits of memory have been shown in long term MDMA users.[49] This may be due to long-term depletion of serotonin, one of the neurotransmitters involved in memory function. However, this is not conclusive proof of neurotoxicity and may be the result of neural plasticity.[50] A recent University of Louisiana study found no significant relationship between depression and recreational ecstasy use.[51][52] The preliminary results from an ongoing Dutch study also indicate that the very moderate use of Ecstasy alleviates symptoms of depression by 28% and improved users' overall mental state. These users also appear to be free of neurological injury of any kind.[53] Drug interactionsIndividuals who have stopped taking any type of SSRI after prolonged medication may not be able to experience the desired effects of MDMA for as long as several months following discontinuation of the medication. This is due to the fact that SSRIs decrease the brain's sensitivity to the presence of serotonin as the brain seeks to reestablish a normal neuro-electrical balance. Most people who die while under the influence of Ecstasy have also consumed significant quantities of at least one other drug. The risk of MDMA-induced death overall is very low. [54] The use of MDMA can be dangerous when combined with other drugs (particularly monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and antiretroviral drugs, in particular ritonavir). Combining MDMA with MAOIs can precipitate hypertensive crisis, as well as serotonin syndrome which can be fatal.[55] MAO-B inhibitors such as deprenyl do not seem to carry these risks when taken at selective doses, and have been used to completely block neurotoxicity in rats. [56] PurityThe purity of a substance sold as Ecstasy is unknown to the typical user. The MDMA content of tablets sold as Ecstasy varies widely between regions and different brands of pills and fluctuates somewhat each year.[57] Pills often contain other active substances which commonly include amphetamine, methamphetamine, caffeine, and usually inactive filler material and coloring, all of which may be comparatively cheap and can help to boost profit overall. In some cases, tablets sold as Ecstasy do not even contain MDMA, chemicals in the Ecstasy Family, or even any kind of stimulant drug. Instead they sometimes contain drugs such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or ketamine amongst others. Some users purchase pill testing kits in an attempt to better understand the make-up of a pill they have purchased. Organizations such as DanceSafe provide pill testing kits.[58] PMAThere have been a number of deaths in which PMA, a potent and highly neurotoxic hallucinogenic amphetamine, has been sold as Ecstasy. PMA is unique in its ability to quickly elevate body temperature and heart rate at relatively low doses, especially in comparison to MDMA.[59] Hence, a user who believes he is consuming 2 120mg pills of MDMA is actually consuming a dose of PMA that is potentially lethal, depending on the purity of the pill. Not only does PMA cause the release of serotonin, but also acts as an MAO-A inhibitor. When combined with an ecstasy-like substance, serotonin syndrome can result. While both PMA and MDMA are currently Schedule I in the U.S, PMA was scheduled more than 10 years before MDMA.[60][61] Additionally, both drugs were rescued from obscurity by the same man, Alexander Shulgin, who at the time was synthesizing new psychoactive chemicals having been granted a license by the DEA to conduct autonomous research. Between the late 1970s and early 1990s, virtually no PMA-related deaths were reported worldwide.[62] It was not until safrole, one of the key ingredients in the original method of MDMA synthesis, was made more difficult to acquire that PMA began to be seen in batches of ecstasy pills in any notable quantity. PMA is almost never sought after as a drug of choice, and this would not be practical to assume for several reasons. One reason is because it is so rare, another is that those who are aware of its existence are usually equally familiar with its unique hazards. The psychological effects of PMA as compared to MDMA are also quite different. PMA lacks the empathogenic qualities of MDMA, and depending on the analogue ingested, may only produce physical stimulation absent of any euphoria (see PMA). HeredityA small percentage of users may be highly sensitive to MDMA; this may make first-time use especially hazardous. This includes, but is not limited to, people with congenital heart defects. Some scientists have suggested that a small percentage of people lack the proper enzymes to break down the drug. One enzyme involved in MDMA's breakdown is CYP2D6, which is deficient or totally absent in 5–10% of the Caucasian population and those of African descent, and in 1–2% of Asians.[63] However, there is no clear evidence linking lack of this enzyme to problems in users, and the connection remains theoretical. Poly substance useTobacco is not known for dangerous interactions with MDMA but carries its own risks, and MDMA users may be prone to overindulgence resulting in short term problems such as sore throat or coughing. Alcohol can enhance dehydration and should be avoided when using MDMA, as common sense would suggest. MDMA is known for being taken in conjunction with other recreational drugs. It is said to complement psychedelics such as LSD and hallucinogenic mushrooms. The two drugs are not taken simultaneously, but rather one is taken as the peak effects of the first are diminishing. A psychedelic such as LSD is usually the first drug taken but this is not always so. Because this practice has become more prevalent, most of the more common combinations have been given nicknames. Some examples include "candy flipping", MDMA combined with LSD[64], also known as trolling (tripping and rolling) , hippie flipping or flower flipping, which is MDMA combined with mushrooms,[citation needed] or triple flipping, which is MDMA with mushrooms and LSD.[citation needed] Pills sold as 'ecstasy' very often contain amphetamine as well as MDMA. In the UK this is so common that pills containing amphetamine are not seen as adulterated, and it is taken for granted that ecstasy pills 'keep you going' for longer than crystal MDMA, due to the 'speed' content of many pills. Clubbers may also take speed during MDMA use to intensify the effects, or after MDMA use to stay awake and energised once tolerance and serotonin depletion has prevented them from gaining any more effect from MDMA. Using MDMA and amphetamine together makes both substances more neurotoxic than using them separately.[citations needed] Clubbers in Europe are increasingly using ketamine during or after MDMA use. Using smaller amounts while on MDMA has little pronounced effect, as the stimulation from the MDMA balances out the depressant qualities of the ketamine. This may however increase the hallucinogenic effects of the MDMA. Clubbers more often use ketamine after the primary effects MDMA have worn off to make the comedown less dysphoric. Many users use mentholated products while taking MDMA, as it is believed to heighten the drug's effects. Examples include menthol cigarettes, Vicks[65] lozenges, etc. This sometimes has deleterious results on the upper respiratory tract.[66] See also

References

Further reading

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||