To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Microwave oven

A microwave oven, or microwave, is a kitchen appliance employing microwave radiation primarily to cook or heat food. Microwave ovens have revolutionized food preparation since their use became widespread in the 1970s. Product highlight

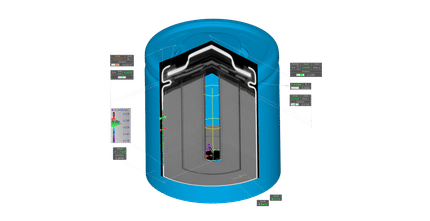

HistoryCooking food with microwaves was discovered by Percy Spencer while building magnetrons for radar sets at Raytheon. He was working on an active radar set when he noticed a strange sensation, and saw that a peanut chocolate bar he had in his pocket started to melt. Although he was not the first to notice this phenomenon, as the holder of 120 patents, Spencer was no stranger to discovery and experiment, and realized what was happening. The radar had melted his candy bar with microwaves. The first food to be deliberately cooked with microwaves was popcorn, and the second was an egg, which exploded in the face of one of the experimenters.[citation needed] On October 8 1945 Raytheon filed a patent for Spencer's microwave cooking process and in 1947, the company built the first microwave oven, the Radarange. It was almost 6 feet (1.8 m) tall and weighed 750 pounds (340 kg). It was water-cooled and consumed 3000 watts, about three times as much as today's microwave ovens. An early commercial model introduced in 1954 generated 1600 watts and sold for $2,000 to $3,000. Raytheon licensed its technology to the Tappan Stove company in 1952. They tried to market a large, 220 volt, wall unit as a home microwave oven in 1955 for a price of $1,295, but it did not sell well. In 1965 Raytheon acquired Amana, which introduced the first popular home model, the countertop Radarange in 1967 at a price of $495. In the 1960s, Litton bought Studebaker's Franklin Manufacturing assets, which had been manufacturing magnetrons and building and selling microwave ovens similar to the Radarange. Litton then developed a new configuration of the microwave, the short, wide shape that is now common. The magnetron feed was also unique. This resulted in an oven that could survive a no-load condition indefinitely. The new oven was shown at a trade show in Chicago, and helped begin a rapid growth of the market for home microwave ovens. Sales volume of 40,000 units for the US industry in 1970 grew to one million by 1975. Market penetration in Japan, which had learned to build less expensive units by re-engineering a cheaper magnetron, was faster. Several other companies joined in the market, and for a time most systems were built by defense contractors, who were the most familiar with the magnetron. Litton was particularly well known in the restaurant business. By the late 1970s the technology had improved to the point where prices were falling rapidly. Formerly found only in large industrial applications, microwave ovens (often referred to informally as simply "microwaves") were increasingly becoming a standard fixture of most kitchens. The rapidly falling price of microprocessors also helped by adding electronic controls to make the ovens easier to use. By the late 1980s they were almost universal in the US and had taken off in many other parts of the globe. Current estimates hold that nearly 95% of American households have a microwave[citation needed]. Currently, the Chinese firm Galanz is the largest maker of microwave ovens in the world[citation needed]. Annually the firm produces over 15 million appliances accounting for 40% of the global market. PrinciplesA microwave oven consists of:

A microwave oven works by passing non-ionizing microwave radiation, usually at a frequency of 2.45 GHz (a wavelength of 12.24 cm), through the food. Microwave radiation is between common radio and infrared frequencies. Water, fat, and other substances in the food absorb energy from the microwaves in a process called dielectric heating. Many molecules (such as those of water) are electric dipoles, meaning that they have a positive charge at one end and a negative charge at the other, and therefore rotate as they try to align themselves with the alternating electric field of the microwaves. This molecular movement creates heat as the rotating molecules hit other molecules and put them into motion. Microwave heating is most efficient on liquid water, and much less so on fats and sugars (which have less molecular dipole moment), and frozen water (where the molecules are not free to rotate). Microwave heating is sometimes explained as a rotational resonance of water molecules, but this is incorrect: such resonance only occurs in water vapor at much higher frequencies, at about 20 gigahertz. Moreover, large industrial/commercial microwave ovens operating at the common large industrial-oven microwave heating frequency of 915 MHz (0.915 GHz), also heat water and food perfectly well. [1] The frequencies used in microwave ovens were chosen based on two constraints. The first is that that they should be in one of the ISM bands set aside for non-communication purposes. Three additional ISM bands exist in the microwave frequencies, but are not used for microwave cooking. Two of them are centered on 5.8 GHz and 24.125 GHz, but are not used for microwave cooking because of the very high cost of power generation at these frequencies. The third, centered on 433.92 MHz, is a narrow band that would require expensive equipment to generate sufficient power without creating interference outside the band, and is only available is some countries. For home use, 2.45 GHz has the advantage over 915 MHz in that 915 MHz is not an ISM band in all countries while 2.45GHz is available worldwide. A common misconception is that microwave ovens cook food from the "inside out". In reality, microwaves are absorbed in the outer layers of food in a manner somewhat similar to heat from other methods. The misconception arises because microwaves penetrate dry non-conductive substances at the surfaces of many common foods, and thus often deposit initial heat more deeply than other methods. Depending on water content, the depth of initial heat deposition may be several centimeters or more with microwave ovens, in contrast to broiling (infrared) or convection heating, which deposit heat thinly at the food surface. Depth of penetration of microwaves is dependent on food composition and the frequency, with lower microwave frequencies penetrating better. Most microwave ovens allow the user to choose between several power levels, including one or more defrosting levels. In most ovens, however, there is no change in the intensity of the microwave radiation; instead, the magnetron is turned on and off in cycles of several seconds at a time. This can actually be observed when microwaving airy foods which may inflate during heating phases, and deflate when the magnetron is turned off. For such ovens, the magnetron is driven by a linear transformer which can only feasibly be switched completely on or off. Newer models have inverter power supplies which use Pulse width modulation to provide truly continuous low-power microwave heating. The cooking chamber itself is a Faraday cage enclosure which prevents the microwaves from escaping into the environment. The oven door is usually a glass panel for easy viewing, but has a layer of conductive mesh to maintain the shielding. Because the size of the perforations in the mesh is much less than the wavelength of 12 cm, most of the microwave radiation cannot pass through the door, while visible light (with a much shorter wavelength) can. With wireless computer networks gaining in popularity, microwave interference has become a concern near wireless networks. Microwave ovens are capable of disrupting wireless network transmissions because the ovens generate radio waves of about 2.45 GHz in the 802.11b/g frequency band, some of them escaping the enclosure despite the presence of the mesh. Microwave ovens are generally used for time efficiency in both industrial applications such as restaurants and at home, rather than for cooking quality, although some modern recipes using microwave ovens rival recipes using traditional ovens and stoves. Professional chefs generally find microwave ovens to be of limited usefulness because the Maillard reactions cannot occur due to the temperature range.[1]. On the other hand, people who want fast cooking times can use microwave ovens to prepare food or to reheat stored food (including commercially available pre-cooked frozen dishes) in only a few minutes. Popcorn is one example of a very popular item with microwave oven users. A variant of the conventional microwave is the convection microwave. A convection microwave is a combination of a standard microwave and a convection oven. It allows food to be cooked quickly, yet come out browned or crisped, as from a convection oven. Convection microwaves are more expensive than a conventional microwave. They are not considered cost-effective if primarily used just to heat drinks or frozen food. They are usually used for cooking a prepared dish. More recently, certain manufacturers have added a high power quartz halogen bulb to their convection microwave models while marketing them under names such as "Speedcook", "Advantium" and "Optimawave" to emphasize their ability to cook food rapidly and with the same browning results typically expected of a conventional oven. This is achieved using the high intensity halogen lights at the top of the microwave to deposit large amounts of infrared radiation to the surface of the food. The food browns while also being heated internally by the microwave radiation and heated through conduction and convection by contact with heated air - produced by the conventional convection portion of the unit. The IR energy which is rapidly delivered to the outer surface of food by the lamps is sufficient to initiate browning and caramelization reactions in a particular food's proteins and carbohydrates, producing a texture and taste much more similar to that typically expected of conventional oven cooking rather than the bland boiled and steamed taste that microwave-only cooking tends to create. In order to aid browning, sometimes an accessory browning tray is used. SizesConsumer microwaves typically come in two types in three sizes.

Increasingly, microwaves are sold with additional features including combining them with convection cooking, "top browning" elements that will brown food (similar to the broiling function on an oven) and even rotisseries in the oven. Most microwaves have white enamel interiors but high end models are often stainless steel, like the original Radarange. EfficiencyA microwave oven only converts part of its electrical input into microwave energy. A typical consumer microwave oven consumes 1100 W of electricity in producing 700 W of microwave power, an efficiency of 64%. The other 400 W are dissipated as heat, mostly in the magnetron tube. Additional power is used to operate the lamps, AC power transformer, magnetron cooling fan, food turntable motor and the control circuits. This waste heat, along with heat from the food, is exhausted as warm air through cooling vents. Safety and controversyThe dominant view has been that microwaved food is more or less as safe to eat as other cooked food. Microwave ovens have become a fairly standard item in most western homes. Microwaving food is fast, energy efficient, and arguably is healthier than traditional means of cooking. Even those who take this view still concede a number of potential safety issues with any food. Safety benefitsCommercial microwave ovens all use a timer in their standard operating mode; when the timer runs out, the oven turns itself off. Microwave ovens heat food without getting hot themselves. Taking a pot off a stove, with the exception of an induction cooktop, leaves a potentially dangerous heating element or trivet that will stay hot for some time. Likewise, when taking a casserole out of a conventional oven, one's arms are exposed to the very hot walls of the oven. A microwave oven does not pose this problem. Food and cookware taken out of a microwave oven is rarely much hotter than 100 °C (212 °F). Cookware used in a microwave oven is often much cooler than the food because the microwaves heat the food directly and the cookware is heated by the food. Food and cookware from a conventional oven, on the other hand, are the same temperature as the rest of the oven; a typical cooking temperature is 180 °C (360 °F). That means that conventional stoves and ovens can cause more serious burns. The lower temperature of cooking (the boiling point of water) is a significant safety benefit compared to baking in the oven or frying, because it eliminates the formation of tars and char, which are carcinogenic. Microwave radiation also penetrates deeper than direct heat, so that the food is heated by its own internal water content. In contrast, direct heat can fry the surface while the inside is still cold. Pre-heating the food in a microwave oven before putting it into the grill or pan reduces the time needed to heat up the food and reduces the formation of carcinogenic char. Uneven heating, deliberate and otherwiseIn a microwave oven, food may be heated for so short a time that it is cooked unevenly, since heat requires time to diffuse through food, and microwaves only penetrate to a limited depth. Microwave ovens are frequently used for reheating previously cooked food, and bacterial contamination may not be killed if the safe temperature is not reached, resulting in foodborne illness. Uneven heating in microwaved food is partly due to the uneven distribution of microwave energy inside the oven, and partly due to the different rates of energy absorption in different parts of the food. The first problem is reduced by a stirrer, a type of fan that reflects microwave energy to different parts of the oven as it rotates, or by a turntable or carousel that turns the food; turntables, however, may still leave spots, such as the center of the oven, which receive uneven energy distribution. The second problem is due to food composition and geometry, and must be addressed by the cook by arranging the food so that it absorbs energy evenly, and periodically testing and shielding any parts of the food that overheat. In some materials with low thermal conductivity, where dielectric constant increases with temperature, microwave heating can cause localized thermal runaway. As an example, uneven heating in frozen foods is a particular problem, since ice absorbs microwave energy to a lesser extent than liquid water, leading to defrosted sections of food warming faster due to more rapid heat deposition there. Due to this phenomenon, microwave ovens set at too-high power levels may even start to cook the edges of the frozen food, while the inside of the food remains frozen. Another case of uneven heating can be observed in baked goods containing berries. In these items, the berries absorb more energy than the drier surrounding bread and also cannot dissipate the heat due to the low thermal conductivity of the bread. The result is frequently the overheating of the berries relative to the rest of the food. The low power levels which mark the "defrost" oven setting are designed to allow time for heat to be conducted from areas which absorb heat more readily to those which heat more slowly. More even heating will take place by placing food off-center on the turntable tray instead of exactly in the center. Microwave heating can be deliberately uneven by design. Some microwavable packages (notably pies) may contain ceramic or aluminum-flake containing materials which are designed to absorb microwaves and heat up (thereby converting microwaves to less penetrating infrared) which aids in baking or crust preparation by depositing more energy shallowly in these areas. Such ceramic patches affixed to cardboard are positioned next to the food, and are typically smokey blue or gray in color, usually making them easily identifiable. Microwavable cardboard packaging may also contain overhead ceramic patches which function in the same way. The technical term for such a microwave-absorbing patch, is a susceptor. Dangers

Liquids, when heated in a microwave oven in a container with a smooth surface, can superheat; that is, reach temperatures that are a few degrees in temperature above their normal boiling point, without actually boiling. The boiling process can start explosively when the liquid is disturbed, such as when the operator takes hold of the container to remove it from the oven or while adding impurities such as powdered creamer or sugar, and can then result in a violent burst of water and vapor resulting in liquid and steam burns. A common myth states that only distilled water can exhibit this behavior; this is not true.[2] Closed containers and eggs can explode when heated in a microwave oven due to the pressure build-up of steam. Products that are heated too long can catch fire. Though this is inherent to any form of cooking, the rapid cooking and unattended nature of microwave oven use results in additional hazard. Microwave oven manuals frequently warn of such hazards, but many of them are difficult to foresee. Because the microwave oven's cavity is enclosed and metal, fires are generally well contained. Simply switching off the oven and allowing the fire to consume available oxygen with the door closed will typically contain damage to the oven itself. Any metal or conductive object placed into the microwave will act as an antenna to some degree, resulting in an electric current. This causes the object to act as a heating element. This effect varies with the object's shape and composition. Any object containing pointed metal can create an electric arc (cause sparks) when microwaved. This includes cutlery, aluminium foil, ceramics decorated with metal, and most anything containing any type of metal. Forks are a good example. This is because the tines of the fork resonate with the microwave radiation and produce high voltage at the tips. This has the effect of exceeding the dielectric breakdown of air, about 3 megavolts per meter (3×106 V/m). The air forms a conductive plasma, which is visible as a spark. The plasma and the tines may then form a conductive loop, which may be a more effective antenna, resulting in a longer lived spark. Any time dielectric breakdown occurs in air, some ozone and nitrogen oxides are formed, both of which are toxic. Microwaving food containing an individual smooth metal object without pointed ends (for example, a spoon) usually does not produce sparking. The effect can be seen clearly on a CD or DVD. The electric current heats the metal film, melting the plastic in the disc and leaving a visible pattern of concentric and radial scars. It can also be illustrated by placing a radiometer inside the cooking chamber, creating plasma inside the vacuum chamber.

Several microwave fires have been noted where Chinese takeout boxes with a metal handle are microwaved. Twist ties containing metal wire and paper are also notoriously dangerous. Another hazard is the resonance of the magnetron tube itself. If the microwave is run without an object to absorb the radiation, a standing wave will form. The energy is reflected back and forth between the tube and the cooking chamber. This may cause the tube to cook itself and burn out. Thus dehydrated food, or food wrapped in metal which does not arc, is problematic without being an obvious fire hazard. Certain foods if carefully arranged can also produce arcing, such as grapes.[3] A naked flame, being made of conductive plasma, will do the same.

Controversial hazards

Some people are concerned with being exposed to the microwave radiation. According to the United States Food and Drug Administration's Center for Devices and Radiological Health, a U.S. Federal standard limits microwave leakage from an oven, for the lifetime of the device, to 5 milliwatts per square centimeter when measured 5 centimeters from the surface of the oven.[4] This is far below the exposure level that is currently considered to be harmful to human health. The radiation produced by a microwave oven is non-ionizing. As such, it does not have the specific cancer risks associated with ionizing radiation such as X-rays, ultraviolet light, and high-energy particles. Any health problems would result from electric currents induced in the body, most prominently cataract formation. Long-term rodent studies to assess cancer risk have so far failed to clearly identify any carcinogenicity from 2.45 GHz microwave radiation at chronic (large fraction of life span) exposure levels, far larger than humans are likely to encounter even from leaking ovens.[5][6] To put the radiation hazard into perspective, the formation of carcinogenic char in conventional frying pan or oven needs to be taken into account (see above). The carcinogens in char are toxicated into carcinogens that are radiomimetic (i.e. cause damage similar to ionizing radiation). Microwaving instead of frying or cooking in the oven eliminates this danger.

There have been studies on the effects of microwave cooking. They show both positive and negative effects on the nutrient contents of food which has been microwaved.

See also

NotesReferences

|

|||||||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Microwave_oven". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. |