Baytron P®– Gateway to a new generation of polymers

Advertisement

Never before in the history of the human race has knowledge expanded so rapidly. The internet and global changes have created the technical and social conditions for this. Yet more knowledge does not inevitably lead to more efficient technology and more reliable products. Other qualities are required to achieve this: Baytron P® is a prime example. With its outstanding properties, this synthetic material opens the door to a new generation of polymers.

Plastics products are light, long-lasting, easy to process and inexpensive. They have, therefore, replaced the classical materials metal and glass in very many areas of application. However, when it comes to the conduction of electricity, metals or semiconductors based on silicon have hitherto been unbeatable. The reason is simple: traditional plastics are good insulators. That is one result of their structure. In contrast to metals, the conduction bands in plastics are so widely spaced that, under normal conditions, no electrons can flow. Nevertheless, scientists have been trying for a long time to adapt the many positive properties of plastics in order to increase their conductivity. Hideki Shirakawa undertook the first experiments in this direction more than a quarter of a century ago. His idea was to produce a plastic material with a structure which enabled the flow of electrons. Polyacetylene was his choice. Building on the work of Karl Ziegler, he produced polyacetylene, but his expectations were not fulfilled. Only when one thousand times the otherwise normal amount of catalyst was used in his laboratory was a silvery, glossy plastics film produced which had properties like those of the semiconductor silicon. Together, Alan G. MacDiarmid, Alan J. Heeger and Hideki Shirakawa investigated the physical principles underlying the phenomenon. They succeeded in drastically improving the electrical conductivity by adding iodine. Later work showed that when using specially prepared catalysts, adding iodine and mechanically stretching the polymer, almost one fifth of the conductivity of copper could be achieved. "Synthetic metals" had been born. Roll-up displays, transparent electrical circuits or strip conductors made of plastics were within reach.

However, it was to be another twenty years before the first laboratory results found practical application. The main reason for the long development time was chemical instability: atmospheric oxygen and moisture decomposed polyacetylene.

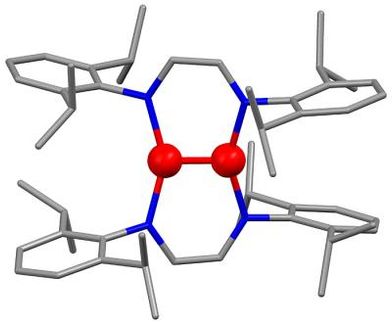

Research workers from universities and industry then synthesized more stable polymers based on pyrrole, aniline and thiophene. In 1993 the Bayer research scientists Friedrich Jonas, Gerhard Heywang and Werner Schmidtberg managed to prepare a particularly long-term stable, electrically conducting, plastics material: poly-3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene. However, there were still processing problems, and many experiments were needed in order to get the plastic "into solution". When this had been achieved, thin films could be cast and processed. A compound of poly-3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene and polystyrenesulfonic acid proved especially useful in practical situations and is marketed as Baytron P®. Areas of use include antistatic coatings.

One example from real life is photographic films. These become electrostatically charged when being wound or rewound, which leads to uncontrolled discharge processes, so-called "flashes". The result is white specks on the developed pictures. The Bayer affiliated company Agfa therefore coats its films with a wafer-thin, but still electrically conductive, layer of Baytron P®. Only small amounts of this blue liquid are required for this purpose. The human eye is unable to perceive the color of the polymer in this ultra-thin layer. Packaging films for electronics components are given an antistatic finish in a similar way.