Caltech researchers show how organic carbon compounds emitted by trees affect air quality

A previously unrecognized player in the process by which gases produced by trees and other plants become aerosols has been discovered by a research team led by scientists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Their research on the creation and effects of these chemicals, called epoxides, is being featured in Science.

Paul Wennberg, the R. Stanton Avery Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Science and Engineering and director of the Ronald and Maxine Linde Center for Global Environmental Science at Caltech, and John Seinfeld, the Louis E. Nohl Professor and professor of chemical engineering, have been studying the role of biogenic emissions — organic carbon compounds given off by plants and trees — in the atmospheric chemical reactions that result in the creation of aerosols.

"If you mix emissions from the city with emissions from plants, they interact to alter the chemistry of the atmosphere," Wennberg notes.

While there's been plenty of attention paid to the effect of emissions from cars and manufacturing, less is understood about what happens to biogenic emissions, especially in places where there are relatively few man-made emissions. That situation is the focus of the research that led to this Science paper. "What we're interested in," Wennberg explains, "is what happens to the chemicals produced by trees once they are emitted into the atmosphere."

In these studies, the research team focused on a chemical called isoprene, which is given off by many deciduous trees. "The king emitters are oaks," Wennberg says. "And the isoprene they emit is one of the reasons that the Smoky Mountains appear smoky."

Isoprene is no minor player in atmospheric chemistry, Wennberg notes. "There is much more isoprene emitted to the atmosphere than all of the gases — gasoline, industrial chemicals — emitted by human activities, with the important exceptions of methane and carbon dioxide," he says. "And isoprene only comes from plants. They make hundreds of millions of tons of this chemical . . . for reasons that we still do not fully understand."

"Much of the emission of isoprene occurs where anthropogenic emissions are limited," adds Caltech graduate student Fabien Paulot, the paper's first author. "The chemistry is very poorly understood."

Once released into the atmosphere, isoprene gets "oxidized or chewed on" by free-radical oxidants such as OH, explains Wennberg. It is this chemistry that is the focus of this new study. In particular, the research was initiated to understand how the oxidation of isoprene can lead to formation of atmospheric particulate matter, so-called secondary organic aerosol. "A small fraction of the isoprene becomes secondary organic aerosol," Seinfeld notes, "but because isoprene emissions are so large, even this small fraction is important."

Up until now, the chemical pathways from isoprene to aerosol were not known. Wennberg, Seinfeld, and their colleagues discovered that this aerosol likely forms from chemicals known as epoxides.

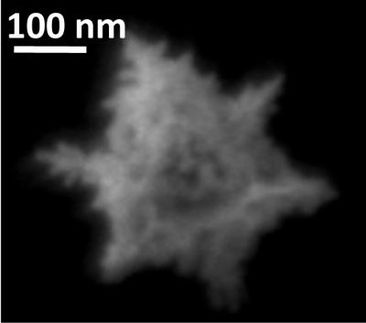

"When these epoxides bump into particles that are acidic, they make glue," Wennberg explains. "The epoxides precipitate out of the atmosphere and stick to the particles, growing them and resulting in lowered visibility in the atmosphere." Because the acidity of the aerosols is generally higher in the presence of anthropogenic activities, the efficiency of converting the epoxides to aerosol is likely higher in polluted environments, illustrating yet another complex interaction between emissions from the biosphere and from humans.

"Particles in the atmosphere have been shown to impact human health, as they are small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs of people. Also, aerosols impact Earth's climate through the scattering and absorption of solar radiation and through serving as the nuclei on which clouds form. So it is important to know where particles come from," notes Seinfeld.

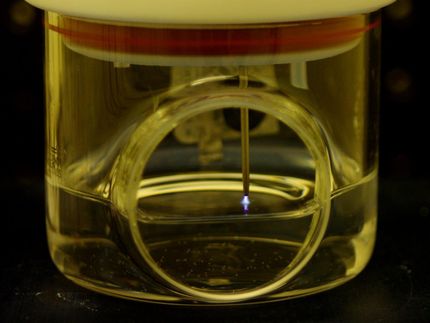

The research team was able to make this scientific leap forward thanks to their development of a new type of chemical ionization mass spectrometry (CIMS), led by coauthor and Caltech graduate student John Crounse. "These new CIMS methods open up a very wide range of possibilities for the study of new sets of compounds that scientists have been largely unable to measure previously, mainly because they decompose when analyzed with traditional techniques."

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic World Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry enables us to detect and identify molecules and reveal their structure. Whether in chemistry, biochemistry or forensics - mass spectrometry opens up unexpected insights into the composition of our world. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of mass spectrometry!

Topic World Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry enables us to detect and identify molecules and reveal their structure. Whether in chemistry, biochemistry or forensics - mass spectrometry opens up unexpected insights into the composition of our world. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of mass spectrometry!