Molybdenum disulfide holds promise for light absorption

Mechanics know molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) as a useful lubricant in aircraft and motorcycle engines and in the CV and universal joints of trucks and automobiles. Rice University engineering researcher Isabell Thomann knows it as a remarkably light-absorbent substance that holds promise for the development of energy-efficient optoelectronic and photocatalytic devices.

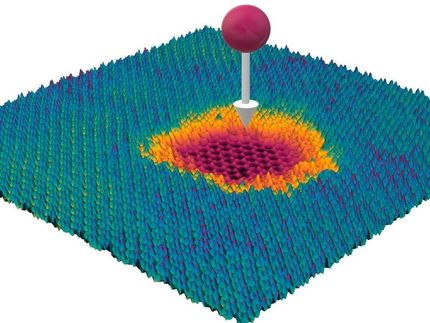

Using a layer of molybdenum disulfide less than one nanometer thick, researchers in Rice University's Thomann lab were able to design a system that absorbed more than 35 percent of incident light in the 400- to 700-nanometer wavelength range. Thomann Group/Rice University

Thomann Group/Rice University

"Basically, we want to understand how much light can be confined in an atomically thin semiconductor monolayer of MoS2," said Thomann, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering and of materials science and nanoengineering and of chemistry. "By using simple strategies, we were able to absorb 35 to 37 percent of the incident light in the 400- to 700-nanometer wavelength range, in a layer that is only 0.7 nanometers thick."

Thomann and Rice graduate students Shah Mohammad Bahauddin and Hossein Robatjazi have recounted their findings in a paper. The research has many applications, including development of efficient and inexpensive photovoltaic solar panels.

"Squeezing light into these extremely thin layers and extracting the generated charge carriers is an important problem in the field of two-dimensional materials," she said. "That's because monolayers of 2-D materials have different electronic and catalytic properties from their bulk or multilayer counterparts."

Thomann and her team used a combination of numerical simulations, analytical models and experimental optical characterizations. Using three-dimensional electromagnetic simulations, they found that light absorption was enhanced 5.9 times compared with using MoS2 on a sapphire substrate.

"If light absorption in these materials was perfect, we'd be able to create all sorts of energy-efficient optoelectronic and photocatalytic devices. That's the problem we're trying to solve," Thomann said.

She is pleased with her lab's progress but concedes that much work remains to be done. "The goal, of course, is 100 percent absorption, and we're not there yet."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.