Atoms looser than expected

Single-electron merry-go-round measures universal atomic force

All the atoms in the universe just got looser, at least in the eyes of humans. Although the laws of physics did not change overnight, our knowledge of how strong atoms are held together did have to be readjusted a bit in light of a new experiment conducted at Harvard University.

By studying how a single electron behaves inside an electronic bottle, Gerald Gabrielse and his colleagues at Harvard were able to calculate a new value for a number six times more precise than the previous measurements called the fine structure constant, which specifies the strength of the electromagnetic force, which holds electrons inside atoms, governs the nature of light and provides all electric and magnetic effects we know, from a flash of lightning to a magnet on a refrigerator. Knowledge of these fundamentals helps scientists and engineers design new kinds of electronic devices-and obtain more profound details on the workings of the universe.

Gabrielse sums up the experiment this way: "Little did we know that the binding energies of all the atoms in the universe were smaller by a millionth of a percent - a lot of energy given the huge number of atoms in the universe."

By studying an individual electron in isolation from any other particle, scientists can eliminate complications of measuring a single object too small to see with even the most powerful microscopes. The Harvard scientists achieved extraordinary conditions of isolation for their individual electron. First of all, the inside of their trap apparatus is pumped free of almost all other particles, establishing a vacuum comparable to that in interplanetary space. The apparatus is chilled to millionths of a degree above absolute zero.

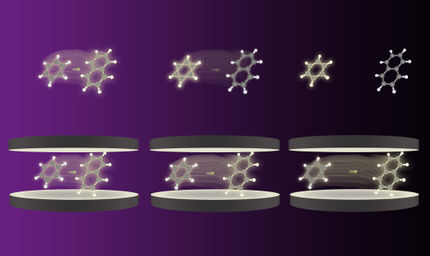

The lone electron and its surrounding cage constitute a sort of gigantic atom. Combined electric and magnetic forces in the trap keep the electron in its circular orbit. In addition to this circular motion, the electron wobbles up and down in the vertical direction, the direction of the magnetic field. It's like a giant merry-go-round, with an electromagnetic trap as the carousel and the electron as the lone horse.

The circuitry used to activate the electrodes keeping the electron pretty much centered in the trap is so sensitive that the system knows when the electron is bobbing upwards and approaching one of the electrodes. A feedback effect using the combined electric and magnetic forces, supplied by electrodes and coils, restricts the motion of the electron. This allows the electron's energy to be measured with great precision.

Original publication: Physical Review Letters 2006.

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.