How Crystal Becomes a Conductor

Advertisement

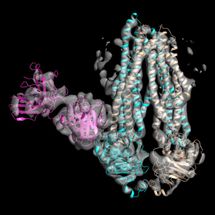

Squeeze a crystal of manganese oxide hard enough, and it changes from an electrical insulator to a conductive metal. In a report published by the journal Nature Materials, researchers use computational modeling to show why this happens.

The results represent an advance in computer modeling of these materials and could shed light on the behavior of similar minerals deep in the Earth, said Warren Pickett, professor of physics at UC Davis and an author on the study.

Manganese oxide is magnetic but does not conduct electricity under normal conditions because of strong interactions between the electrons surrounding atoms in the crystal, Pickett said. But under pressures of about one megabar, manganese oxide transitions to a metallic state.

Pickett and colleagues Richard Scalettar at UC Davis, Jan Kunes at the University of Augsburg, Germany, Alexey Lukoyanov at the Ural State Technical University, Russia, and Vladimir Anisimov at the Institute of Metal Physics in Yekaterinburg, Russia, built and ran computational models of manganese oxide.

Using the model, the researchers were able to test different explanations for the transition and identify the microscopic mechanism responsible. They found that when the atoms are forced together under high pressure, the magnetic properties of the manganese atoms become unstable and collapse, freeing the electrons to move through the crystal.

Manganese oxide has similar properties to iron oxide and silicates (silicon oxides), which make up a major part of the Earth's crust and mantle. Understanding how these materials behave under enormous pressures deep underground could help geologists understand the Earth's interior, Pickett said.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.