To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Aniline

Aniline, phenylamine or aminobenzene is an organic compound with the formula C6H5NH2. It is the simplest and one of the most important aromatic amines, being used as a precursor to more-complex chemicals. Its main application is in the manufacture of polyurethane. Like most volatile amines, it possesses the somewhat unpleasant odour of rotten fish and also has a burning aromatic taste; it is a highly-acrid poison. It ignites readily, burning with a smoky flame.

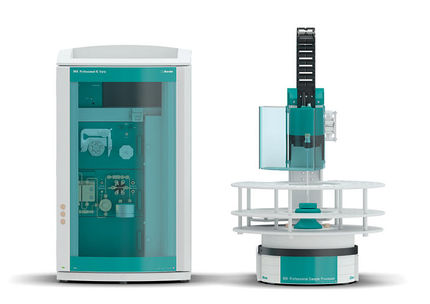

Product highlight

Structure and synthesisConsisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is usually produced in industry in two steps from benzene: First, benzene is nitrated using a concentrated mixture of nitric acid and sulfuric acid at 50 to 60 °C, which gives nitrobenzene. In the second step, the nitrobenzene is hydrogenated, typically at 600 °C in presence of a nickel catalyst to give aniline. As an alternative, aniline is also prepared from phenol and ammonia, the phenol being derived from cumene. [1] DerivativesMany derivatives of aniline can be prepared in similar fashion. In commerce, three brands of aniline are distinguished--aniline oil for blue, which is pure aniline; aniline oil for red, a mixture of equimolecular quantities of aniline and ortho- and para-toluidines; and aniline oil for safranine, which contains aniline and ortho-toluidine, and is obtained from the distillate (échappés) of the fuchsine fusion. PropertiesOxidationAniline is colourless, it slowly oxidizes and resinifies in air, giving a red-brown tint to aged samples. The oxidation of aniline has been carefully investigated. In alkaline solution, azobenzene results, whereas arsenic acid produces the violet-colouring matter violaniline. Chromic acid converts it into quinone, whereas chlorates, in the presence of certain metallic salts (especially of vanadium), give aniline black. Hydrochloric acid and potassium chlorate give chloranil. Potassium permanganate in neutral solution oxidizes it to nitrobenzene, in alkaline solution to azobenzene, ammonia and oxalic acid, in acid solution to aniline black. Hypochlorous acid gives 4-aminophenol and para-amino diphenylamine. BasicityAniline is a weak base. Aromatic amines such as aniline are, in general, much weaker bases than aliphatic amines. Aniline reacts with strong acids to form anilinium (or phenylammonium) ion (C6H5-NH3+). The sulfate forms beautiful white plates. Although aniline is weakly basic, it precipitates zinc, aluminium, and ferric salts, and, on warming, expels ammonia from its salts. AcylationAniline reacts with carboxylic acids[2] or more readily with acyl chlorides such as acetyl chloride to give amides. The amides formed from aniline are sometimes called anilides, for example CH3-CO-NH-C6H5 is acetanilide. Antifebrin (acetanilide), an anti-pyretic and analgesic, is obtained by the reaction of acetic acid and aniline. N-alkyl derivativesAniline combines directly with alkyl iodides to form secondary and tertiary amines. Monomethyl and dimethyl aniline are colourless liquids prepared by heating aniline, aniline hydro-chloride and methyl alcohol in an autoclave at 220 °C. They are of great importance in the colour industry. Monomethyl aniline boils at 193-195 °C, dimethyl aniline at 192 °C. Sulfur derivativesBoiled with carbon disulfide, it gives sulfocarbanilide (diphenyl thiourea), CS(NHC6H5)2, which may be decomposed into phenyl isothiocyanate, C6H5CNS, and triphenyl guanidine, C6H5N=C(NHC6H5)2. Like phenols, aniline derivatives are highly susceptible to electrophilic substitution reactions. For example, sulfonation of aniline produces sulfanilic acid, which can be converted to sulfanilamide. Sulfanilamide is one of the sulfa drugs that were widely used as antibacterials in the early 20th century. Reaction with sulfuric acid at 180°C produces sulfanilic acid, NH2C6H4SO3H. DiazotizationAniline and its ring-substituted derivatives react with nitrous acid to form diazonium salts. Through these, the -NH2 group of aniline can be conveniently converted to -OH, -CN, or a halide via Sandmeyer reactions. Other reactionsIt reacts with nitrobenzene to produce phenazine in the Wohl-Aue reaction. UsesThe great commercial value of aniline was due to the readiness with which it yields, directly or indirectly, dyestuffs. The discovery of mauve in 1856 by William Henry Perkin was the first of a series of dyestuffs that are now to be numbered by hundreds. Reference should be made to the articles dyeing, fuchsine, safranine, indulines, for more details on this subject. In addition to its use as a precursor to dyestuffs, it is a starting-product for the manufacture of many drugs, such as paracetamol (acetaminophen, Tylenol). It is used to stain neural RNA blue in the Nissl stain. At the present time, the largest market for aniline is preparation of methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI), some 85% of aniline serving this market. Other uses include rubber processing chemicals (9%), herbicides (2%), and dyes and pigments (2%).[3] HistoryAniline was first isolated from the destructive distillation of indigo in 1826 by Otto Unverdorben[4] , who named it crystalline. In 1834, Friedrich Runge (Pogg. Ann., 1834, 31, p. 65; 32, p. 331) isolated from coal tar a substance that produced a beautiful blue colour on treatment with chloride of lime, which he named kyanol or cyanol. In 1841, C. J. Fritzsche showed that, by treating indigo with caustic potash, it yielded an oil, which he named aniline, from the specific name of one of the indigo-yielding plants, Indigofera anil, anil being derived from the Sanskrit nīla, dark-blue, and nīlā, the indigo plant. About the same time N. N. Zinin found that, on reducing nitrobenzene, a base was formed, which he named benzidam. August Wilhelm von Hofmann investigated these variously-prepared substances, and proved them to be identical (1855), and thenceforth they took their place as one body, under the name aniline or phenylamine. Its first industrial-scale use was in the manufacture of mauveine, a purple dye discovered in 1856 by Hofmann's student William Henry Perkin. At the time of mauveine's discovery, aniline was an expensive laboratory compound, but it was soon prepared "by the ton" using a process previously discovered by Antoine Béchamp.[5] The synthetic dye industry grew rapidly as new aniline-based dyes were discovered in the late 1850s and 1860s. p-Toluidine, an aniline derivative, can be used in qualitative analysis to prepare carboxylic acid derivatives. ToxicologyAniline is toxic by inhalation of the vapour, absorption through the skin or swallowing. It causes headache, drowsiness, cyanosis, and mental confusion, and, in severe cases, can cause convulsions. Prolonged exposure to the vapour or slight skin exposure over a period of time affects the nervous system and the blood, causing tiredness, loss of appetite, headache, and dizziness.[6] Oil mixtures containing rapeseed oil denatured with aniline have been clearly linked by epidemiological and analytic chemical studies to the toxic oil syndrome that hit Spain in the spring and summer of 1981, in which 20,000 became acutely ill, 12,000 were hospitalized, and more than 350 died in the first year of the epidemic. The precise etiology though remains unknown. Some authorities class aniline as a carcinogen, although the IARC lists it in Group 3 (not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans) due to the limited and contradictory data available. References

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain. Categories: Aromatic amines | Dyes | IARC Group 3 carcinogens |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Aniline". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||