Uncovering the real dirt on granular flow

Advertisement

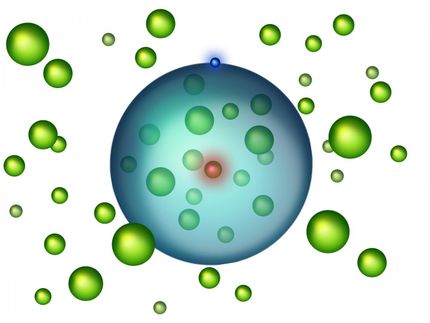

A handful of sand contains countless grains, which interact with each other via friction and impact forces as they slip through your fingers. When a handful becomes a load in an excavator bucket, those interactions multiply exponentially.

By solving large sets of differential equations, researchers can predict how sand or other granular material will move. Assistant Professor Dan Negrut and his team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Simulation-Based Engineering Laboratory are developing innovative computer simulation methods for parallel computers to analyze granular material motion much faster than is possible with current technologies.

Even a supercomputer takes days to run a simulation charting the motion of millions of sand grains. Negrut hopes his simulation will analyze millions of grains in a single day, if not a matter of hours. The difference lies in how parallel computers approach the task. The central processing unit of a regular computer processes information sequentially, so grains are analyzed one after another. Parallel computers that rely on the graphics-processing unit (GPU) can simultaneously execute one instruction multiple times. This is how a graphics card processes pixels to render scene after scene in video games.

Negrut uses GPU computation to determine in-parallel sand movement. He and his students built a custom computer that handles almost 50,000 parallel computational threads at any given time. Currently, the team is working on detecting which particles collide with each other when, for example, granular material is scooped up by an excavator or driven over by a car.

"The task is challenging because there are hundreds of thousands of collisions you have to track," Negrut says, adding the preliminary data on collision detection developed by graduate students Toby Heyn and Justin Madsen look promising.

Once Negrut and his students can accurately predict collisions between individual particles, they will determine what frictional contact force is actually at work between the particles. For this, they will collaborate with Professor Alessandro Tasora from the University of Parma, Italy.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.