Nanoburgers with promising flaws

DESY team finds surprising defects in tiny metal particles, which could stimulate the development of more efficient catalysts

Advertisement

catalysts are indispensable in many industries: they speed up chemical reactions, making them economically viable. They often consist of tiny particles, just a few nanometres across, to which molecules attach themselves, making it easier for them to form a bond with another reagent. The catalysts themselves are left unchanged. One class of nanocatalysts consists of the precious metals platinum and rhodium and is used, for example, in the purification of waste gases, in hydrogen production and in fuel cells.

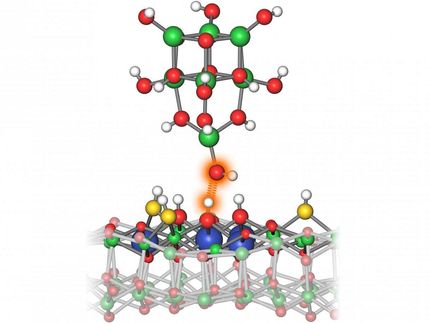

The Nano-Burger in action: the two “halves' of the platinum-rhodium catalyst interact with reagents in this simulation.

Science Communication Lab for DESY

The team led by DESY physicist Andreas Stierle has been studying such platinum-rhodium catalysts for quite some time. However, when they analysed the particles again using X-rays, they were surprised to find that some of the nanoparticles are not tiny, homogeneous lumps, but consist of an upper and a lower half – like the two halves of a burger bun. Although the two halves are stuck together, the nature of this bond and how it affects the catalytic properties of the nanoparticles was unclear.

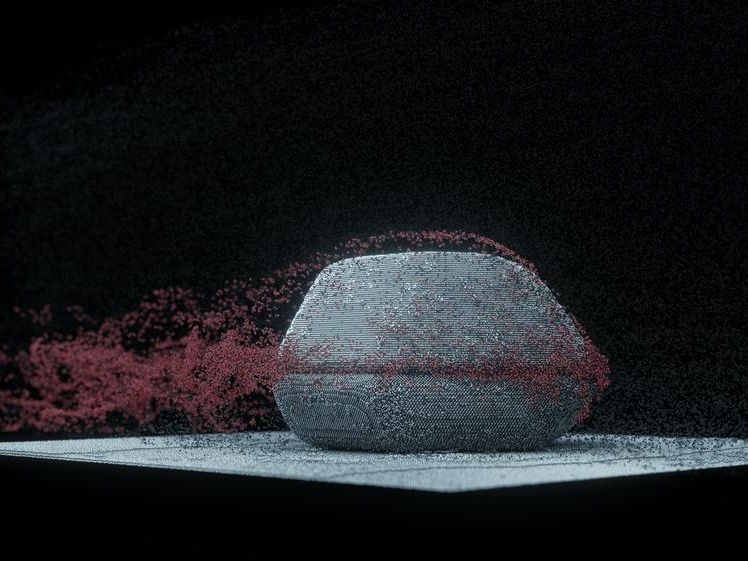

To work this out, Stierle's team designed an experiment at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility ESRF in Grenoble. ‘It produces an extremely narrow X-ray beam that can be used to study individual nanoparticles,’ explains Stierle. Specifically, the researchers used a method known as Bragg Coherent Diffraction Imaging (BCDI), in which the X-ray beam creates a special diffraction pattern as it passes through the nanoparticle, and this is recorded by a detector. ‘Special algorithms can then be used to reconstruct how the atoms are arranged in the crystal lattice and where they deviate from the regular structure – distortions, defects and dislocations in the crystal lattice,’ explains Ivan Vartanyants, who supervised the reconstructions.

What made their experiment different was that the measurements were performed while the nanocatalysts were active. The group directed a stream of carbon monoxide and oxygen to pass over the nanoparticles, on whose surface the gas was converted into CO2 – at temperatures of more than 400 degrees Celsius. ‘These experiments were extremely difficult; we had to keep the nanoparticles fixed to within ten nanometres so that the X-ray beam always illuminated the entire particle,’ explains first author Lydia Bachmann, who is studying this topic as part of her PhD. ‘To do this, we had to make sure that the conditions were absolutely steady.’

The outcome was unexpected: the experts discovered pronounced crystal defects where the upper and lower halves of the nanoburgers meet. The two boundary surfaces did not fit perfectly on top of each other; atoms were missing around the outer edges. These gaps cause all the atoms in the vicinity to shift, significantly distorting and displacing the crystal lattice.

What was truly remarkable was that these ‘flaws’ had an extremely positive effect on the catalytic properties of the nanoburgers. ‘The defects serve as unique absorption sites for molecules,’ explains co-author Thomas Keller. ‘Molecules such as oxygen adhere very well to them, which increases the effectiveness of the catalyst.’ In the future, these findings could help industry to develop more efficient and effective catalysts – through deliberate ‘defect engineering’ to create as many binding sites as possible on the nanoparticles, where molecules can be converted.

The team plans to continue working towards this goal. Among other things, the scientists would like to know how the defects in the nanoburgers are created in the first place. ‘The particles are produced at temperatures of 1000 degrees Celsius, and we suspect that the defects form when the particles cool down rapidly,’ says team leader Stierle. ‘It appears that, because the particles are so small, thermal stresses arise in them, which then disrupt the stacking order of the crystal layers.’ If this process were understood in detail, it might be possible to optimise the manufacturing process to create specific crystal defects that are particularly effective at increasing the catalytic effect of the nanoparticles.

In a few years’ time, experiments at DESY’s planned X-ray source PETRA IV could help. The successor to the current PETRA III ring will produce X-rays that are much finer and more narrowly focussed than those at the ESRF. This will make it possible to study much smaller nanoparticles than has previously been possible. ‘The nanoburgers that we examined in Grenoble were around 100 nanometres in size,’ explains Stierle. ‘The catalytic particles used in industry today are generally only 10 to 20 nanometres across. PETRA IV would allow us to analyse such industrially more relevant particles in the future and observe them in action in real time.’

Original publication

Lydia J. Bachmann, Dmitry Lapkin, Jan-Christian Schober, Daniel Silvan Dolling, Young Yong Kim, Dameli Assalauova, Nastasia Mukharamova, Jagrati Dwivedi, Tobias U. Schulli, Thomas F. Keller, Ivan A. Vartanyants, Andreas Stierle; "Coherent X-ray Diffraction Imaging of a Twinned PtRh Catalyst Nanoparticle under Operando Conditions"; ACS Nano, 2025-6-25