How graphene nanoparticles improve the resolution of microscopes

Small particles, big effects

Advertisement

Conventional light microscopes cannot distinguish structures when they are separated by a distance smaller than, roughly, the wavelength of light. Superresolution microscopy, developed since the 1980s, lifts this limitation, using fluorescent moieties. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research have now discovered that graphene nano-molecules can be used to improve this microscopy technique. These graphene nano-molecules offer a number of substantial advantages over the materials previously used, making superresolution microscopy even more versatile.

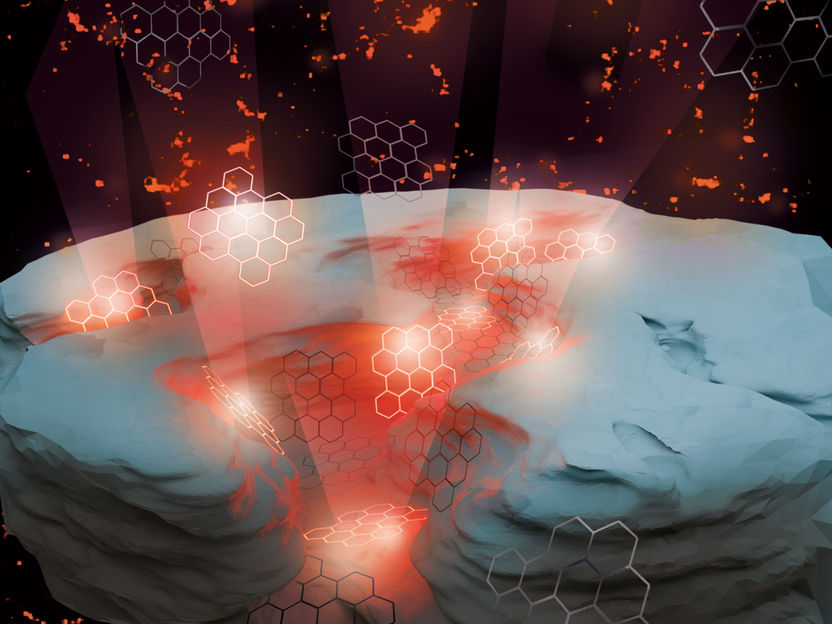

Nanoparticles of graphene flash irregularly when excited with light. This results in higher resolution in microscopy.

© MPI-P

Microscopy is an important investigation method, in physics, biology, medicine, and many other sciences. However, it has one disadvantage: its resolution is limited by physical principles. Structures can only be imaged if they are separated by a distance greater than half the wavelength of light. With blue light, this corresponds to a distance of approximately 200 nanometers, i.e., 200 millionths of a millimeter.

This limit can be circumvented using superresolution microscopy. Today there are a number of different such approaches. In the type of superresolution microscopy applied here, fluorescent particles are excited by light and re-emit light at a slightly different wavelength, i.e. a slightly different color. The position of these fluorescent particles can be determined with higher precision than given by the wavelength of the light: If they are blinking randomly, two neighbouring particles typically do not light up simultaneously – this means that their signals do not overlap and thus the positions of the individual particles can be determined independently of each other, so that even at very small distances the particles can be imaged separately, i.e. "resolved". Researchers at the MPI-P have now shown that nanoparticles from graphene – so-called nanographenes, consisting of a carbon layer only one atom thick - have properties that are ideal for this special microscopy technique.

In the past, several fluorescent materials have been used for this type of microscopy, including dyes, so-called quantum dots, and fluorescent proteins. Nanographenes are as good as the best of these materials in terms of their optical properties. In addition to their excellent optical properties, nanographenes are non-toxic, very small, and, most notably and different from all other materials, their flashing frequency is robust and independent of their environment. This means that nanographene can be used in air, aqueous solutions and other solvents - making it a very versatile fluorophore. Nanographenes can further be readily modified so that they only adhere to certain interesting locations on a sample, e.g., a specific organelle in a cell.

"We have compared nanographene with the gold standard in this microscopy technique - the organic dye Alexa 647," says Prof. Mischa Bonn, director at the MPI-P. "We found that nanographene is as efficient as this dye, i.e., it can convert as much of the incident light into a different color, but doesn’t require a specifically tailored environment that Alexa requires.“

To test the nanographene produced at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, the scientists collaborated with Prof. Christoph Cremer's group at the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB) in Mainz. The researchers prepared a glass surface with nanometer-sized fissures. Here, nanographene particles were applied, which were mainly deposited in the gaps. In comparison with conventional microscopy, they were able to show that the resolution could be increased by a factor of 10 using graphene nanoparticles.

The scientists see the development of their material as an important step in superresolution microscopy.