To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Molecular mechanicsThe term molecular mechanics refers to the use of Newtonian mechanics to model molecular systems. The potential energy of all systems in molecular mechanics is calculated using force fields. Molecular mechanics can be used to study small molecules as well as large biological systems or material assemblies with many thousands to millions of atoms. All-atomistic molecular mechanics methods have the following properties:

Variations on this theme are possible; for example, many simulations have historically used a "united-atom" representation in which methyl and methylene groups were represented as a single particle, and large protein systems are commonly simulated using a "bead" model that assigns two to four particles per amino acid. Product highlight

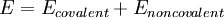

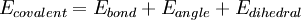

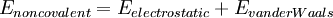

Functional FormThe following functional abstraction, known as a potential function or force field in Chemistry, calculates the molecular system's potential energy (E) in a given conformation as a sum of individual energy terms.

where the components of the covalent and noncolvalent contributions are given by the following summations:

The exact functional form of the potential function, or force field, depends on the particular simulation program being used. Generally the bond and angle terms are modeled as harmonic potentials centered around equilibrium bond-length values derived from experiment or theoretical calculations of electronic structure performed with software which does ab-initio type calculations such as Gaussian. For accurate reproduction of vibrational spectra, the Morse potential can be used instead, at computational cost. The dihedral or torsional terms typically have multiple minima and thus cannot be modeled as harmonic oscillators, though their specific functional form varies with the implementation. This class of terms may include "improper" dihedral terms, which function as correction factors for out-of-plane deviations (for example, they can be used to keep benzene rings planar). The non-bonded terms are much more computationally costly to calculate in full, since a typical atom is bonded to only a few of its neighbors, but interacts with every other atom in the molecule. Fortunately the van der Waals term falls off rapidly - it is typically modeled using a "6-12 Lennard-Jones potential", which means that attractive forces fall off with distance as r-6 and repulsive forces as r-12, where r represents the distance between two atoms. Generally a cutoff radius is used to speed up the calculation so that atom pairs whose distances are greater than the cutoff have a van der Waals interaction energy of zero. The electrostatic terms are notoriously difficult to calculate well because they do not fall off rapidly with distance, and long-range electrostatic interactions are often important features of the system under study (especially for proteins). The basic functional form is the Coulomb potential, which only falls off as r-1. A variety of methods are used to address this problem, the simplest being a cutoff radius similar to that used for the van der Waals terms. However, this introduces a sharp discontinuity between atoms inside and atoms outside the radius. Switching or scaling functions that modulate the apparent electrostatic energy are somewhat more accurate methods that multiply the calculated energy by a smoothly varying scaling factor from 0 to 1 at the outer and inner cutoff radii. Other more sophisticated but computationally intensive methods are known as particle mesh Ewald (PME) and the multipole algorithm. In addition to the functional form of each energy term, a useful energy function must be assigned parameters for force constants, van der Waals multipliers, and other constant terms. These terms, together with the equilibrium bond, angle, and dihedral values, partial charge values, atomic masses and radii, and energy function definitions, are collectively known as a force field. Parameterization is typically done through agreement with experimental values and theoretical calculations results. Each force field is parameterized to be internally consistent, but the parameters are generally not transferable from one force field to another. Areas of applicationThe prototypical Molecular Mechanics application is energy minimization. That is, the force field is used as an optimization criterion and the (local) minimum searched by an appropriate algorithm (e.g. steepest descent). Global energy optimization can be accomplished using simulated annealing, the Metropolis algorithm and other Monte Carlo methods, or using different deterministic methods of discrete or continuous optimization. The main aim of optimization methods is finding the lowest energy conformation of a molecule or identifying a set of low-energy conformers that are in equilibrium with each other. The force field represents only the enthalpic component of free energy, and only this component is included during energy minimization. However, the analysis of equilibrium between different states requires also conformational entropy be included, which is possible but rarely done. Other applications of MM include potential energy mapping and ligand docking simulations. Molecular Mechanics and Molecular Dynamics (MD) are related but different. Main purpose of MD is modeling of molecular motions, although it is also applied for optimization, for example using simulated annealing. MM implements more "static" energy minimization methods to study the potential energy surfaces of different molecular systems. However, MM can also provide important dynamic parameters, such as energy barriers between different conformers or steepness of a potential energy surface around a local minimum. MD and MM are usually based on the same classical force fields. But MD may also be based on quantum chemical methods like DFT. MM is also loosely used to define a set of techniques in molecular modeling. Environment and SolvationThere are several ways of defining the environment surrounding the molecule or molecules of interest in molecular mechanics. A system can be simulated in vacuum (known as a gas-phase simulation) with no surrounding environment at all, but this is usually not desirable because it introduces artifacts in the molecular geometry, especially in charged molecules. Surface charges that would ordinarily interact with solvent molecules instead interact with each other, producing molecular conformations that are unlikely to be present in any other environment. The "best" way to solvate a system is to place explicit water molecules in the simulation box with the molecules of interest and treat the water molecules as interacting particles like those in the molecule. A variety of water models exist with increasing levels of complexity, representing water as a simple hard sphere (a united-atom approach), as three separate particles with fixed bond angles, or even as four or five separate interaction centers to account for unpaired electrons on the oxygen atom. Unsurprisingly, the more complex the water model, the more computationally intensive the simulation. A compromise approach has been found in implicit solvation, which replaces the explicitly represented water molecules with a mathematical expression that reproduces the average behavior of water molecules (or other solvents such as lipids). This method is useful for preventing artifacts that arise from vacuum simulations and reproduces bulk solvent properties well, but cannot reproduce situations in which individual water molecules have interesting interactions with the molecules under study. Software PackagesLimited list; many more are available See alsoForce field in Chemistry References

Categories: Molecular physics | Computational chemistry | Intermolecular forces |

|

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Molecular_mechanics". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. |