To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

Enthalpy

The term enthalpy is composed of the prefix en-, meaning to "put into", plus the Greek word -thalpein, meaning "to heat", although the original definition is thought to have stemmed from the word, "enthalpos" (ἐνθάλπος).[1] It is often calculated as a differential sum, describing the changes within exo- and endothermic reactions, which minimize at equilibrium. Product highlight

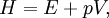

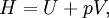

HistoryOver the history of thermodynamics, several terms have been used to denote what is now known as the enthalpy of a system. Originally, it was thought that the word "enthalpy" was created by Benoit Paul Émile Clapeyron and Rudolf Clausius through the publishing of the Clausius-Clapeyron relation in "The Mollier Steam Tables and Diagrams" in 1927, but it was later published that the earliest recording of the word was in 1875, by Josiah Willard Gibbs in the publication "Physical Chemistry: an Advanced Treatise"[2], although it is not referenced in Gibbs' works directly[3]. In 1909, Keith Landler discussed Gibbs' work on the 'heat function for constant pressure' and noted that Heike Kamerlingh Onnes had coined its modern name from the Greek word "enthalpos" (ενθαλπος) meaning "to put heat into." [1] Original definitionThis is the heat change which occurs when 1 mol of a substance reacts completely with oxygen to form products at 298 K and 1 atm. The function H was introduced by the Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes in early 20th century in the following form: where E represents the energy of the system. In the absence of an external field, the enthalpy may be defined, as it is generally known, by: where (all units given in SI)

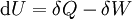

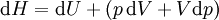

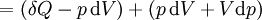

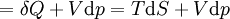

Application and extended formulaOverviewIn terms of thermodynamics, enthalpy can be calculated by determining the requirements for creating a system from "nothingness"; the mechanical work required, pV differs, based upon the constancy of conditions present at the creation of the thermodynamic system. Internal energy, U, must be supplied to remove particles from a surrounding in order to allow space for the creation of a system, providing that environmental variables, such as pressure (p) remain constant. This internal energy also includes the energy required for activation and the breaking of bonded compounds into gaseous species. This process is calculated within enthalpy calculations as U + pV, to label the amount of energy or work required to "set aside space for" and "create" the system; describing the work done by both the reaction or formation of systems, and the surroundings. For systems at constant pressure, the change in enthalpy is the heat received by the system plus the non-mechanical work that has been done. Therefore, the change in enthalpy can be devised or represented without the need for compressive or expansive mechanics; for a simple system, with a constant number of particles, the difference in enthalpy is the maximum amount of thermal energy derivable from a thermodynamic process in which the pressure is held constant. The term pV is the work required to displace the surrounding atmosphere in order to vacate the space to be occupied by the system. RelationshipsAs an expansion of the first law of thermodynamics, enthalpy can be related to several other thermodynamic formulae. As with the original definition of the first law;

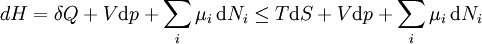

As a differentiating expression, the value of H can be defined as Where

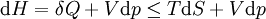

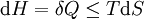

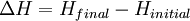

For a process that is not reversible, the second law of thermodynamics states that the increase in heat δQ is less than or equal to the product TdS of temperature T and the increase in entropy dS; thus It is seen that, if a thermodynamic process is isobaric (i.e., occurs at constant pressure), then dp is zero and thus The difference in enthalpy is the maximum thermal energy attainable from the system in an isobaric process. This explains why it is sometimes called the heat content. That is, the integral of dH over any isobar in state space is the maximum thermal energy attainable from the system. If, in addition, the entropy is held constant as well, i.e., dS = 0, the above equation becomes: with the equality holding at equilibrium. It is seen that the enthalpy for a general system will continuously decrease to its minimum value, which it maintains at equilibrium. In a more general form, the first law describes the internal energy with additional terms involving the chemical potential and the number of particles of various types. The differential statement for dH is then: where μi is the chemical potential for an i-type particle, and Ni is the number of such particles. It is seen that, not only must the Vdp term be set to zero by requiring the pressures of the initial and final states to be the same, but the μidNi terms must be zero as well, by requiring that the particle numbers remain unchanged. Any further generalization will add even more terms whose extensive differential term must be set to zero in order for the interpretation of the enthalpy to hold. Heats of reactionThe total enthalpy of a system cannot be measured directly; the enthalpy change of a system is measured instead. Enthalpy change is defined by the following equation: where

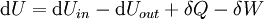

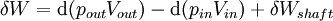

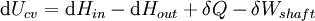

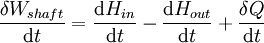

For an exothermic reaction at constant pressure, the system's change in enthalpy is equal to the energy released in the reaction, including the energy retained in the system and lost through expansion against its surroundings. In a similar manner, for an endothermic reaction, the system's change in enthalpy is equal to the energy absorbed in the reaction, including the energy lost by the system and gained from compression from its surroundings. A relatively easy way to determine whether or not a reaction is exothermic or endothermic is to determine the sign of ΔH. If ΔH is positive, the reaction is endothermic, that is heat is absorbed by the system due to the products of the reaction having a greater enthalpy than the reactants. The product of an endothermic reaction will be cold to the touch. On the other hand if ΔH is negative, the reaction is exothermic, that is the overall decrease in enthalpy is achieved by the generation of heat. The product of an exothermic reaction will be warm to the touch. Although enthalpy is commonly used in engineering and science, it is impossible to measure directly, as enthalpy has no datum (reference point). Therefore enthalpy can only accurately be used in a closed system. However, few real world applications exist in closed isolation, and it is for this reason that two or more closed systems cannot be compared using enthalpy as a basis, although sometimes this is done erroneously. Open systemsIn thermodynamic open systems, matter may flow in and out of the system boundaries. The first law of thermodynamics for open systems states: the increase in the internal energy of a system is equal to the amount of energy added to the system by matter flowing in and by heating, minus the amount lost by matter flowing out and in the form of work done by the system. The first law for open systems is given by: where Uin is the average internal energy entering the system and Uout is the average internal energy leaving the system The region of space enclosed by open system boundaries is usually called a control volume, and it may or may not correspond to physical walls. If we choose the shape of the control volume such that all flow in or out occurs perpendicular to its surface, then the flow of matter into the system performs work as if it were a piston of fluid pushing mass into the system, and the system performs work on the flow of matter out as if it were driving a piston of fluid. There are then two types of work performed: flow work described above which is performed on the fluid (this is also often called pV work) and shaft work which may be performed on some mechanical device. These two types of work are expressed in the equation: Substitution into the equation above for the control volume cv yields: The definition of enthalpy, H, permits us to use this thermodynamic potential to account for both internal energy and pV work in fluids for open systems: During steady-state operation of a device (see turbine, pump, and engine), the expression above may be set equal to zero. This yields a useful expression for the power generation or requirement for these devices in the absence of chemical reactions: This expression is described by the diagram above. Standard enthalpy changesDefinitionsStandard enthalpy change of combustion

Standard enthalpy change of hydrogenation

Standard enthalpy change of formation

Standard enthalpy change of reaction

A common standard enthalpy change is the standard enthalpy change of formation, which has been determined for a vast number of substances. The enthalpy change of any reaction under any conditions can be computed, given the standard enthalpy change of formation of all of the reactants and products. Other types of standard enthalpy change include combustion (standard enthalpy change of combustion), neutralisation (standard enthalpy change of neutralisation), melting (standard enthalpy change of fusion), vaporisation/condensation (standard enthalpy change of vaporisation), atomisation (standard enthalpy change of atomisation), mixing (standard enthalpy change of mixing), dissolution (standard enthalpy change of solution), and denaturation (standard enthalpy change of denaturation). Examples: Inorganic compounds (at 25 °C)

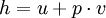

Specific enthalpyThe specific enthalpy of a working mass is a property of that mass used in thermodynamics, defined as Notes

References

See also

Categories: Thermodynamics | Enthalpy |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Enthalpy". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

where u is the specific internal energy, p is the pressure, and v is specific volume. In other words,

where u is the specific internal energy, p is the pressure, and v is specific volume. In other words,