Levitating magnet may yield new approach to clean energy

Advertisement

A new experiment that reproduces the magnetic fields of the Earth and other planets has yielded its first significant results. The findings confirm that its unique approach has some potential to be developed as a new way of creating a power-producing plant based on nuclear fusion — the process that generates the sun's prodigious output of energy.

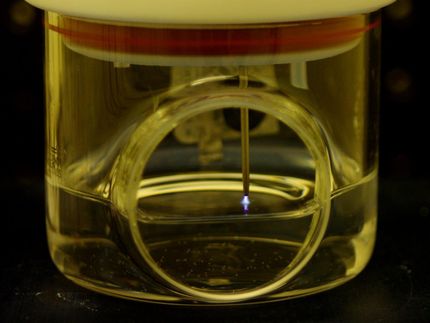

The new results come from an experimental device on the MIT campus, inspired by observations from space made by satellites. Called the Levitated Dipole Experiment, or LDX, a joint project of MIT and Columbia University, it uses a half-ton donut-shaped magnet about the size and shape of a large truck tire, made of superconducting wire coiled inside a stainless steel vessel. This magnet is suspended by a powerful electromagnetic field, and is used to control the motion of the 10-million-degree-hot electrically charged gas, or plasma, contained within its 16-foot-diameter outer chamber.

The results, published in the Nature Physics, confirm the counter-intuitive prediction that inside the device's magnetic chamber, random turbulence causes the plasma to become more densely concentrated — a crucial step to getting atoms to fuse together — instead of becoming more spread out, as usually happens with turbulence. This "turbulent pinching" of the plasma has been observed in the way plasmas in space interact with the Earth's and Jupiter's magnetic fields, but has never before been recreated in the laboratory.

Most experiments in fusion around the world use one of two methods: tokamaks, which use a collection of coiled magnets surrounding a donut-shaped chamber to confine the plasma, or inertial fusion, using high-powered lasers to blast a tiny pellet of fuel at the device's center. But LDX takes a different approach. "It's the first experiment of its kind," says MIT senior scientist Jay Kesner, MIT's physics research group leader for LDX, who co-directs the project with Michael E. Mauel, professor of applied physics at Columbia University's Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science.

The results of the experiment show that this approach "could produce an alternative path to fusion," Kesner says, though more research will be needed to determine whether it would be practical. For example, though the researchers have measured the plasma's high density, new equipment still needs to be installed to measure its temperature, and ultimately a much larger version would have to be built and tested.

Kesner cautions that the kind of fuel cycle planned for other types of fusion reactors such as tokamaks, which use a mixture of two forms of "heavy" hydrogen called deuterium and tritium, should be easier to achieve and will likely be the first to go into operation. The deuterium-deuterium fusion planned for devices based on the LDX design, if they ever become practical, would likely make this "a second-generation approach," he says.