To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

MagnetA magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. A "hard" or "permanent" magnet is one which stays magnetized for a long time, such as magnets often used on refrigerator doors. Permanent magnets occur naturally in some rocks, particularly lodestone, but are now more commonly manufactured. A "soft" or "impermanent" magnet is one which loses its memory of previous magnetizations. "Soft" magnetic materials are often used in electromagnets to enhance (often hundreds or thousands of times) the magnetic field of a wire that carries an electrical current and is wrapped around the magnet; the field of the "soft" magnet increases with the current. Two measures of a material's magnetic properties are its magnetic moment and its magnetization. A material without a permanent magnetic moment can, in the presence of magnetic fields, be attracted (paramagnetic), or repelled (diamagnetic). Liquid oxygen is paramagnetic; graphite is diamagnetic. Paramagnets tend to intensify the magnetic field in their vicinity, whereas diamagnets tend to weaken it. "Soft" magnets, which are strongly attracted to magnetic fields, can be thought of as strongly paramagnetic; superconductors, which are strongly repelled by magnetic fields, can be thought of as strongly diamagnetic. Product highlightBackground on the physics of magnetism and magnets

Magnetic fieldThe magnetic field (usually denoted B) is a vector field (that is, some vector at every point of space and time), with SI units of teslas. The magnetic field at given time and place is a vector, so it has a magnitude and a direction. The direction is defined as the direction that a compass needle would point if it were held there, and the magnitude (also called strength) is defined to be proportional to how strongly the compass needle gets pushed in that direction. Magnetic momentThe magnetic moment (also called magnetic dipole moment, and usually denoted μ) of a magnet is a vector which (loosely speaking) characterizes how magnetic it is. The direction of the magnetic moment points from the magnet's south pole to its north pole, and the magnitude relates to how strong and how far apart these poles are. To be more exact, the magnetic moment manifests itself in two ways. First, the magnet creates a certain magnetic field, and the strength of that field at any given point is proportional to the magnitude of the magnet's magnetic moment.[1] Second, when the magnet is put into an "external" magnetic field created by a different source, it will respond by feeling a torque pushing it so that the magnetic moment points parallel to the field (see above). The amount of torque felt in a given magnetic field is proportional to the magnetic moment. A wire in the shape of a circle with area A and carrying current I is a magnet, which has a magnetic moment with magnitude equal to IA. MagnetizationThe magnetization of an object is its magnetic moment per unit volume, which is a vector field, usually denoted M, with units A/m. The reason it is a vector field, and not just a vector, is that the different sections of a bar magnet will in general be magnetized with different directions and strengths (for example, due to domains, see below). A good bar magnet may have a magnetic moment of 0.1 A·m² and a volume of 1 cm³, or 0.000001 m³, and therefore an average magnetization of 100,000 A/m. Iron can have a magnetization of around a million A/m. Magnetic polesAlthough for many purposes it is convenient to think of a magnet as having north and south magnetic poles, the concept of poles should not be taken too literally. While electric charges can be positive or negative, there is no particle which is "north" or "south".[2]. If a bar magnet is broken in half, in an attempt to separate the north and south poles, the result will be two bar magnets, each of which has both a north and south pole. At best, the idea of north and south poles is a sometimes-useful simplified model for understanding a magnet's behavior. This is called the "Gilbert Model" of a magnetic dipole.[3] However, this model does not always give correct results. A much better model is the "Ampère Model", where all magnetization is due to macroscopic "bound currents", also called "Ampèrearian currents". For example, for a uniformly magnetized bar magnet in the shape of a cylinder, the net effect of the atomic currents is to make the magnet behave as if there is a sheet of current flowing around the cylinder, with local flow direction normal to the cylinder axis. A right-hand rule due to Ampère tells us how the currents flow, for a given magnetic moment. Align the thumb of your right hand along the magnetic moment, and with that hand grasp the cylinder. Your fingers will then point along the direction of current flow. Pole naming conventionsThe north pole of the magnet is the pole which (when the magnet is freely suspended) points towards the magnetic north pole (in northern Canada). Since opposite poles (north and south) attract while like poles (north and north, or south and south) repel, the Earth's present geographic north is thus actually its magnetic south. Confounding the situation further, the Earth's magnetic field occasionally reverses itself. In order to avoid this confusion, the terms positive and negative poles are sometimes used instead of north and south, respectively. As a practical matter, in order to tell which pole of a magnet is north and which is south, it is not necessary to use the earth's magnetic field at all. For example, one calibration method would be to compare it to an electromagnet, the poles of which can be identified via the right-hand rule. Descriptions of magnetic behaviorsThere are many forms of magnetic behavior, and all materials exhibit at least one of these behaviors. Magnets vary both in the permanency of their magnetization, and in the strength and orientation of the magnetic field that is created. This section describes, qualitatively, the primary different types of magnetic behavior that materials can show. The physics underlying each of these behaviors is described in the next section below, and can also be found in more detail in their respective articles.

Physics of magnetic behaviorsOverviewMagnetism, at its root, arises from two sources:

In magnetic materials, the most important sources of magnetization are, more specifically, the electrons' orbital angular motion around the nucleus, and the electrons' intrinsic magnetic moment (see Electron magnetic dipole moment). The other potential sources of magnetism are much less important: For example, the nuclear magnetic moments of the nuclei in the material are typically thousands of times smaller than the electrons' magnetic moments, so they are negligible in the context of the magnetization of materials. (Nuclear magnetic moments are important in other contexts, particularly in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).) Ordinarily, the countless electrons in a material are arranged such that their magnetic moments (both orbital and intrinsic) cancel out. This is due, to some extent, to electrons combining into pairs with opposite intrinsic magnetic moments (as a result of the Pauli exclusion principle; see Electron configuration), or combining into "filled subshells" with zero net orbital motion; in both cases, the electron arrangement is so as to exactly cancel the magnetic moments from each electron. Moreover, even when the electron configuration is such that there are unpaired electrons and/or non-filled subshells, it is often the case that the various electrons in the solid will contribute magnetic moments that point in different, random directions, so that the material will not be magnetic. However, sometimes (either spontaneously, or due to an applied external magnetic field) each of the electron magnetic moments will be, on average, lined up. Then the material can produce a net total magnetic field, which can potentially be quite strong. The magnetic behavior of a material depends on its structure (particularly its electron configuration, for the reasons mentioned above), and also on the temperature (at high temperatures, random thermal motion makes it more difficult for the electrons to maintain alignment). Physics of paramagnetismIn a paramagnet there are unpaired electrons, i.e. atomic or molecular orbitals with exactly one electron in them. While paired electrons are required by the Pauli exclusion principle to have their intrinsic ('spin') magnetic moments pointing in opposite directions (summing to zero), an unpaired electron is free to align its magnetic moment in any direction. When an external magnetic field is applied, these magnetic moments will tend to align themselves in the same direction as the applied field, thus reinforcing it. Physics of diamagnetismIn a diamagnet, there are no unpaired electrons, so the intrinsic electron magnetic moments cannot produce any bulk effect. In these cases, the magnetization arises from the electrons' orbital motions, which can be understood classically as follows: When a material is put in a magnetic field, the electrons circling the nucleus will experience, in addition to their Coulomb attraction to the nucleus, a Lorentz force from the magnetic field. Depending on which direction the electron is orbiting, this force may increase the centripetal force on the electrons, pulling them in towards the nucleus, or it may decrease the force, pulling them away from the nucleus. This effect systematically increases the orbital magnetic moments that were aligned opposite the field, and decreases the ones aligned parallel to the field (in accordance with Lenz's law). This results in a small bulk magnetic moment, with an opposite direction to the applied field. Note that this description is meant only as a heuristic; a proper understanding requires a quantum-mechanical description. Note that all materials, including paramagnets, undergo this orbital response. However, in a paramagnet, this response is overwhelmed by the much stronger opposing response described above (i.e., alignment of the electrons' intrinsic magnetic moments). Physics of ferromagnetismA ferromagnet, like a paramagnet, has unpaired electrons. However, in addition to the electrons' intrinsic magnetic moments wanting to be parallel to an applied field, there is also in these materials a tendency for these magnetic moments to want to be parallel to each other. Thus, even when the applied field is removed, the electrons in the material can keep each other continually pointed in the same direction. Every ferromagnet has its own individual temperature, called the Curie temperature, or Curie point, above which it loses its ferromagnetic properties. This is because the thermal tendency to disorder overwhelms the energy-lowering due to ferromagnetic order. Magnetic Domains

The magnetic moment of atoms in a ferromagnetic material cause them to behave something like tiny permanent magnets. They stick together and align themselves into small regions of more or less uniform alignment called magnetic domains or Weiss domains. Magnetic domains can be observed with Magnetic force microscope to reveal magnetic domain boundaries that resemble white lines in the sketch.There are many scientific experiments that can physically show magnetic fields. When a domain contains too many molecules, it becomes unstable and divides into two domains aligned in opposite directions so that they stick together more stably as shown at the right. When exposed to a magnetic field, the domain boundaries move so that the domains aligned with the magnetic field grow and dominate the structure as shown at the left. When the magnetizing field is removed, the domains may not return to a unmagnetized state. This results in the ferromagnetic material being magnetized, forming a permanent magnet. When magnetized strongly enough that the prevailing domain overruns all others to result in only one single domain, the material is magnetically saturated. When a magnetized ferromagnetic material is heated to the Curie point temperature, the molecules are agitated to the point that the magnetic domains lose the organization and the magnetic properties they cause cease. When the material is cooled, this domain alignment structure spontaneously returns as the material develops its crystalline structure. Physics of antiferromagnetism

In an antiferromagnet, unlike a ferromagnet, there is a tendency for the intrinsic magnetic moments of neighboring valence electrons to point in opposite directions. When all atoms are arranged in a substance so that each neighbor is 'anti-aligned', the substance is antiferromagnetic. Antiferromagnets have a zero net magnetic moment, meaning no field is emitted by them. Antiferromagnets are less common compared to the other types of behaviors, and are mostly observed at low temperatures. In varying temperatures, antiferromagnets can be seen to exhibit diamagnetic and ferrimagnetic properties. In some materials, neighboring electrons want to point in opposite directions, but there is no geometrical arrangement in which each pair of neighbors is anti-aligned. This is called a spin glass, and is an example of geometrical frustration. Physics of ferrimagnetism

Like ferromagnetism, ferrimagnets retain their magnetization in the absence of a field. However, like antiferromagnets, neighboring pairs of electron spins like to point in opposite directions. These two properties are not contradictory, due to the fact that in the optimal geometrical arrangement, there is more magnetic moment from the sublattice of electrons which point in one direction, than from the sublattice which points in the opposite direction. The first discovered magnetic substance, magnetite, was originally believed to be a ferromagnet; Louis Néel disproved this, however, with the discovery of ferrimagnetism. Other types of magnetismThere are various other types of magnetism, such as and spin glass (mentioned above), superparamagnetism, superdiamagnetism, and metamagnetism. Common uses of magnets

Magnetization and demagnetizationFerromagnetic materials can be magnetized in the following ways:

Permanent magnets can be demagnetized in the following ways:

In an electromagnet which uses a soft iron core, ceasing the flow of current will eliminate the magnetic field. However, a slight field may remain in the core material as a result of hysteresis. Types of permanent magnets

Magnetic metallic elementsMany materials have unpaired electron spins, and the majority of these materials are paramagnetic. When the spins interact with each other in such a way that the spins align spontaneously, the materials are called ferromagnetic (what is often loosely termed as "magnetic"). Due to the way their regular crystalline atomic structure causes their spins to interact, some metals are (ferro)magnetic when found in their natural states, as ores. These include iron ore (magnetite or lodestone), cobalt and nickel, as well the rare earth metals gadolinium and dysprosium (when at a very low temperature). Such naturally occurring (ferro)magnets were used in the first experiments with magnetism. Technology has since expanded the availability of magnetic materials to include various manmade products, all based, however, on naturally magnetic elements. CompositesCeramic or ferriteCeramic, or ferrite, magnets are made of a sintered composite of powdered iron oxide and barium/strontium carbonate ceramic. Due to the low cost of the materials and manufacturing methods, inexpensive magnets (or nonmagnetized ferromagnetic cores, for use in electronic component such as radio antennas, for example) of various shapes can be easily mass produced. The resulting magnets are noncorroding, but brittle and must be treated like other ceramics. AlnicoAlnico magnets are made by casting or sintering a combination of aluminium, nickel and cobalt with iron and small amounts of other elements added to enhance the properties of the magnet. Sintering offers superior mechanical characteristics, whereas casting delivers higher magnetic fields and allows for the design of intricate shapes. Alnico magnets resist corrosion and have physical properties more forgiving than ferrite, but not quite as desirable as a metal. Injection moldedInjection molded magnets are a composite of various types of resin and magnetic powders, allowing parts of complex shapes to be manufactured by injection molding. The physical and magnetic properties of the product depend on the raw materials, but are generally lower in magnetic strength and resemble plastics in their physical properties. FlexibleFlexible magnets are similar to injection molded magnets, using a flexible resin or binder such as vinyl, and produced in flat strips or sheets. These magnets are lower in magnetic strength but can be very flexible, depending on the binder used. Rare earth magnets'Rare earth' (lanthanoid) elements have a partially occupied f electron shell (which can accommodate up to 14 electrons.) The spin of these electrons can be aligned, resulting in very strong magnetic fields, and therefore these elements are used in compact high-strength magnets where their higher price is not a concern. Samarium-cobaltSamarium-cobalt magnets are highly resistant to oxidation, with higher magnetic strength and temperature resistance than alnico or ceramic materials. Sintered samarium-cobalt magnets are brittle and prone to chipping and cracking and may fracture when subjected to thermal shock. Neodymium-iron-boron (NIB)Neodymium magnets, more formally referred to as neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, have the highest magnetic field strength, but are inferior to samarium cobalt in resistance to oxidation and temperature. This type of magnet has traditionally been expensive, due to both the cost of raw materials and licensing of the patents involved. This high cost limited their use to applications where such high strengths from a compact magnet are critical. Use of protective surface treatments such as gold, nickel, zinc and tin plating and epoxy resin coating can provide corrosion protection where required. Beginning in the 1980s, NIB magnets have increasingly become less expensive and more popular in other applications such as children's magnetic building toys. Even tiny neodymium magnets are very powerful and have important safety considerations.[4] Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) and single-chain magnets (SCMs)In the 1990s it was discovered that certain molecules containing paramagnetic metal ions are capable of storing a magnetic moment at very low temperatures. These are very different from conventional magnets that store information at a "domain" level and theoretically could provide a far denser storage medium than conventional magnets. In this direction research on monolayers of SMMs is currently under way. Very briefly, the two main attributes of an SMM are:

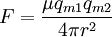

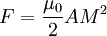

Most SMM's contain manganese, but can also be found with vanadium, iron, nickel and cobalt clusters. More recently it has been found that some chain systems can also display a magnetization which persists for long times at relatively higher temperatures. These systems have been called single-chain magnets. Nano-structured magnetsSome nano-structured materials exhibit energy waves called magnons that coalesce into a common ground state in the manner of a Bose-Einstein condensate. See results from NIST published April 2005,[5] or[6] ElectromagnetsAn electromagnet in its simplest form, is a wire that has been coiled into one or more loops, known as a solenoid. When electric current flows through the wire, a magnetic field is generated. It is concentrated near (and especially inside) the coil, and its field lines are very similar to those for a magnet. The orientation of this effective magnet is determined via the right hand rule. The magnetic moment and the magnetic field of the electromagnet are proportional to the number of loops of wire, to the cross-section of each loop, and to the current passing through the wire. If the coil of wire is wrapped around a material with no special magnetic properties (i.e., cardboard), it will tend to generate a very weak field. However, if it is wrapped around a "soft" ferromagnetic material, such as an iron nail, then the net field produced can result in a several hundred- to thousandfold increase of field strength. Uses for electromagnets include particle accelerators, electric motors, junkyard cranes, and magnetic resonance imaging machines. Some applications involve configurations more than a simple magnetic dipole; for example, quadrupole magnets are used to focus particle beams. Units and calculations in magnetismHow we write the laws of magnetism depends on which set of units we employ. For most engineering applications, MKS or SI (Système International) is common. Two other sets, Gaussian and CGS-emu, are the same for magnetic properties, and are commonly used in physics. In all units it is convenient to employ two types of magnetic field, B and H, as well as the magnetization M, defined as the magnetic moment per unit volume. (1) The magnetic induction field B is given in SI units of T (tesla). B is the true magnetic field, whose time-variation produces, by Faraday's Law, circulating electric fields (which the power companies sell). B also produces a deflection force on moving charged particles (as in TV tubes). The tesla is equivalent to the magnetic flux (in webers) per unit area (in meters squared), thus giving B the unit of a flux density. In CGS the unit of B is G (gauss). One T equals 104 G. (2) The magnetic field H is given in SI units of ampere-turns/meter (A-turn/m). The "turns" appears because when H is produced by a current-carrying wire, its value is proportional to the number of turns of that wire. In CGS the unit of H is Oe (oersted). One A-turn/m equals 4π x 10-3 Oe. (3) The magnetization M is given in SI units of ampere/meter (A/m). In CGS the unit of M is the emu, or electromagnetic unit. One A/m equals 10-3 emu. A good permanent magnet can have a magnetization as large as a million A/m. Magnetic fields produced by current-carrying wires would require comparably huge currents per unit length, one reason we employ permanent magnets and electromagnets. (4) In SI units, the relation B=μ0(H+M) holds, where μ0 is the permeability of space, which equals 4π x 10-7 tesla∙meter/ampere. In CGS it is written as B=H+4πM. Materials that are not permanent magnets usually satisfy the relation M=χH in SI, where χ is the (dimensionless) magnetic susceptibility. Most non-magnetic materials have a relatively small χ (on the order of a millionth), but soft magnets can have χ's on the order of hundreds or thousands. For materials satisfying M=χH, we can also write B=μ0(1+χ)H=μ0μrH=μH, where μr=1+χ is the (dimensionless) relative permeability and μ = μ0μr is the magnetic permeability. Both hard and soft magnets have a more complex, history-dependent, behavior described by what are called hysteresis loops, which give either B vs H or M vs H. In CGS M=χH, but χ(SI) = 4πχ(CGS), and μ = μr. Caution: In part because there are not enough Roman and Greek symbols, there is no commonly agreed upon symbol for magnetic pole strength and magnetic moment. The symbol m has been used for both pole strength (unit = A-m, where here "m is for meter") and for magnetic moment (unit = A-m²). The symbol μ has been used in some texts for magnetic permeability and in other texts for magnetic moment. We will use μ for magnetic permeability and m for magnetic moment. For pole strength we will employ qm. For a bar magnet of cross-section A with uniform magnetization M along its axis, the pole strength is given by qm=MA, so that M can be thought of as a pole strength per unit area. Fields of a magnetFar away from a magnet, the magnetic field created by that magnet is almost always described (to a good approximation) by a dipole field characterized by its total magnetic moment. This is true regardless of the shape of the magnet, so long as the magnetic moment is nonzero. One characteristic of a dipole field is that the strength of the field falls off inversely with the cube of the distance from the magnet's center. Closer to the magnet, the magnetic field becomes more complicated, and more dependent on the detailed shape and magnetization of the magnet. Formally, the field can be expressed as a multipole expansion: A dipole field, plus a quadrupole field, plus an octupole field, etc. At close range, many different possible fields are possible. For example, for a long, skinny bar magnet with its north pole at one end and south pole at the other, the magnetic field near either end falls off inversely with the square of the distance from that pole. Calculating the magnetic forceCalculating the attractive or repulsive force between two magnets is, in the general case, an extremely complex operation, as it depends on the shape, magnetization, orientation and separation of the magnets. Force between two magnetic polesThe force between two magnetic poles is given by:

where

The pole description is useful to practicing magneticians who design real-world magnets, but real magnets have a pole distribution more complex than a single north and south. Therefore, implementation of the pole idea is not simple. In some cases, one of the more complex formulae given below will be more useful. Force between two nearby attracting surfaces of area A and equal but opposite magnetizations M

where

Force between two bar magnetsThe force between two identical cylindrical bar magnets placed end-to-end is given by:

where

B0= See also

Online references

Printed references1. "positive pole n." The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. 2. Wayne M. Saslow, "Electricity, Magnetism, and Light", Academic (2002). ISBN 0-12-619455-6. Chapter 9 discusses magnets and their magnetic fields using the concept of magnetic poles, but it also gives evidence that magnetic poles don't really exist in ordinary matter. Chapters 10 and 11, following what appears to be a 19th century approach, use the pole concept to obtain the laws describing the magnetism of electric currents. 3. Edward P. Furlani, "Permanent Magnet and Electromechanical Devices: Materials, Analysis and Applications", Academic Press Series in Electromagnetism (2001). ISBN 0-12-269951-3. Footnotes and References

|

||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Magnet". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. |

[1]

[1]

[2]

[2]

![F=\left[\frac {B_0^2 A^2 \left( L^2+R^2 \right)} {\pi\mu_0L^2}\right] \left[{\frac 1 {x^2}} + {\frac 1 {(x+2L)^2}} - {\frac 2 {(x+L)^2}} \right]](images/math/e/a/0/ea0c076f1c59249aba590d07b31da41e.png) [3]

[3]

M relates the flux density at the pole to the magnetization of the magnet.

M relates the flux density at the pole to the magnetization of the magnet.