Magnetism guides individual atoms

Potential for controlled atomic movement in nanotechnology and data storage

Advertisement

Normally, individual atoms move on surfaces rather randomly - influenced primarily by the symmetry of the surface. This process, known as "diffusion", plays a central role in the production of semiconductors, in catalysts or in the construction of nanostructures. Researchers have long suspected that magnetism could also influence the movement of individual atoms. Scientists at Kiel University (CAU) and the University of Hamburg have now been able to demonstrate this experimentally for the first time: On a magnetic surface, atoms can be steered along a specific direction. The results were published in "Nature Communications".

Targeted movement instead of chance

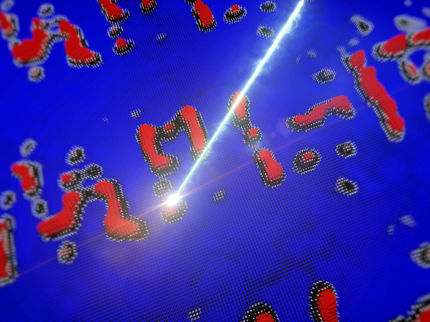

The team was able to prove this using a scanning tunneling microscope. At temperatures close to absolute zero (four Kelvin), they placed individual atoms such as cobalt, rhodium and iridium on a manganese layer that is exactly one atomic layer thick and was previously vapor-deposited onto a rhenium surface. This structure creates a particularly well-defined, magnetically ordered surface in which the magnetic properties of the individual rows of atoms are precisely known.

It turned out that although this layer has a symmetrical, hexagonal structure, the atoms on it did not move randomly in one of the six possible directions after a short current pulse, but always along magnetic rows - even if the atoms themselves are not magnetic, as in the case of rhodium or iridium.

Quantum mechanics provides the explanation

"Such movements were previously predicted theoretically, but never proven experimentally," says Professor Stefan Heinze from the Institute of Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics at Kiel University. Together with his colleague Dr. Soumyajyoti Haldar, he carried out quantum mechanical calculations on the supercomputers of the National Supercomputing Alliance (NHR) in Berlin to explain the phenomenon.

Their simulations show: It is energetically easier for the atoms to move along the magnetic rows than across them. The reason for this lies in a magnetic interaction between the atom and the atoms on the surface: both can be imagined as tiny bar magnets. In the case of atoms of magnetic elements such as cobalt, this interaction is caused by their own magnetic moment. In the case of atoms of non-magnetic elements such as rhodium or iridium, a small magnetic moment is only caused by the interaction with the surface and influences the direction of movement. The atoms therefore prefer to move along the magnetic rows of the surface. Until now, researchers have assumed that magnetism plays no role in the movement of individual atoms - this assumption has now been refuted by the new results.

"Magnetic properties of a surface can influence the mobility of individual atoms," says Soumyajyoti Haldar. "This opens up new possibilities for specifically controlling atomic movements - for applications in nanotechnology, data storage or the development of new materials, for example."

Note: This article has been translated using a computer system without human intervention. LUMITOS offers these automatic translations to present a wider range of current news. Since this article has been translated with automatic translation, it is possible that it contains errors in vocabulary, syntax or grammar. The original article in German can be found here.