New hybrid inks permit printed, flexible electronics without sintering

Advertisement

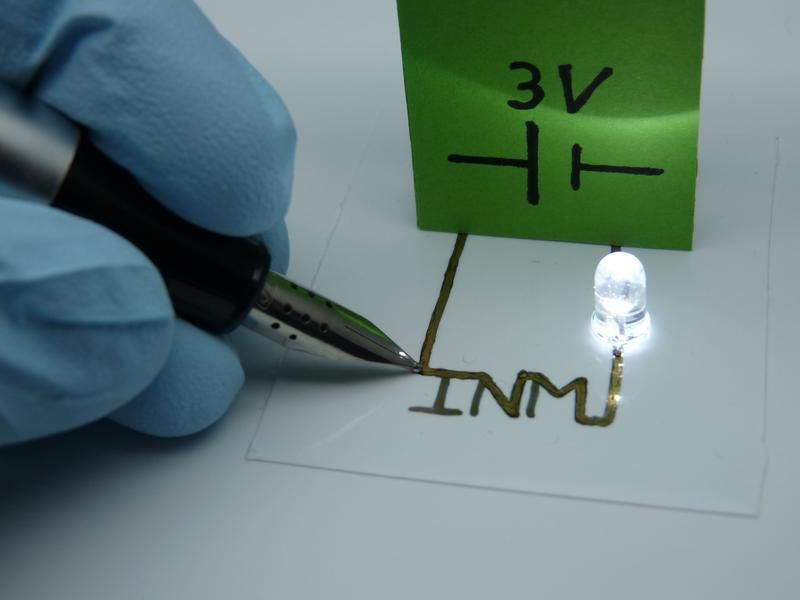

Research scientists at INM - Leibniz Institute for New Materials have combined the benefits of organic and inorganic electronic materials in a new type of hybrid inks. This allows electronic circuits to be applied to paper directly from a pen, for example.

New hybrid inks permit printed, flexible electronics without sintering.

INM

The electronics of the future will be printed. Flexible circuits can be produced inexpensively on foil or paper using printing processes and permit futuristic designs with curved diodes or input elements. This requires printable electronic materials that can be printed and retain a high level of conductivity during usage in spite of their curved surfaces. Some tried and tested materials include organic, conductive polymers and nanoparticles made of conductive oxides (TCOs). Research scientists at INM – Leibniz-Institute for New Materials have now combined the benefits of organic and inorganic electronic materials in a new type of hybrid inks. This allows electronic circuits to be applied to paper directly from a pen, for example.

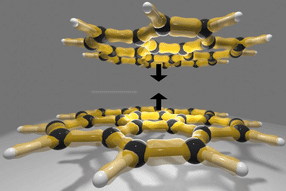

To create their hybrid inks, the research scientists coated nanoparticles made of metals with organic, conductive polymers and suspended them in mixtures of water and alcohol. These suspensions can be applied directly on paper or foil using a pen and they dry without any further processing to form electrical circuits.

“Electrically conductive polymers are used in OLEDs, for example, which can also be manufactured on flexible substrates,” explains Tobias Kraus, Head of the research group Structure Formation at INM. “The combination of metal and nano-particles that we introduce here combines mechanical flexibility with the robustness of a metal and increases the electrical conductivity”.

The developers combine the organic polymers with gold or silver nanoparticles. The organic compounds have three functions: “On the one hand, the compounds serve as ligands, ensuring that the nanoparticles remain suspended in the liquid mixture; any agglomeration of particles would have a negative effect on the printing process. Simultaneously, the organic ligands ensure that the nanoparticles have a good arrangement when drying. Ultimately, the organic compounds act as ´hinges´: if the material is bent, they maintain the electrical conductivity. In a layer of metal particles without the polymer sheath the electrical conductivity would quickly be lost when the material is bent,” the material scientist Kraus continues. Due to the combination of both materials, when bent, the electrical conductivity is greater all in all than in a layer that is made purely of conductive polymer or a layer made purely of metal nanoparticles.

“Metal nanoparticles with ligands are already printed to form electronics today,” explains the physical chemist Kraus, adding that the shells mostly had to be removed by a sintering process because, while on the one hand they control the arrangement of the nanoparticles, on the other hand, they are not conductive. He added that this was difficult in the case of carrier materials that are sensitive to temperature such as paper or polymer films since these would be damaged during the sintering process. Kraus summarizes the results of his research, saying, “Our new hybrid inks are conductive as soon as they have dried as well as being particularly mechanically flexible and they do not require sintering”.