Nanotechnology could promote hydrogen economy

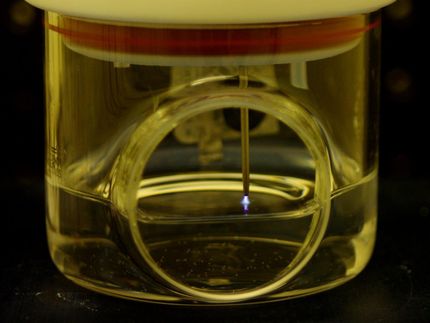

In a new twist, Rutgers scientists are using nanotechnology in chemical reactions that could provide hydrogen for tomorrow's fuel-cell powered clean energy vehicles. In a paper in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, researchers at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, describe how they make a finely textured surface of the metal iridium that can be used to extract hydrogen from ammonia, then captured and fed to a fuel cell. The metal's unique surface consists of millions of pyramids with facets as tiny as five nanometers across, onto which ammonia molecules can nestle like matching puzzle pieces. This sets up the molecules to undergo complete and efficient Decomposition.

"The nanostructured surfaces we're examining are model catalysts," said Ted Madey, State of New Jersey professor of surface science in the physics department at Rutgers. "They also have the potential to catalyze chemical reactions for the chemical and pharmaceutical industries."

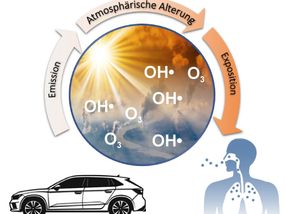

A major obstacle to establishing the "hydrogen economy" is the safe and cost-effective storage and transport of hydrogen fuel. The newly discovered process could contribute to the solution of this problem. Handling hydrogen in its native form, as a light and highly flammable gas, poses daunting engineering challenges and would require building a new fuel distribution infrastructure from scratch.

By using established processes to bind hydrogen with atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia molecules, the resulting liquid could be handled much like today's gasoline and diesel fuel. Then using nanostructured catalysts based on the one being developed at Rutgers, pure hydrogen could be extracted under the vehicle's hood on demand, as needed by the fuel cell, and the remaining nitrogen harmlessly released back into the atmosphere. The carbon-free nature of ammonia would also make the fuel cell catalyst less susceptible to deactivation.

When developing industrial catalysts, scientists and engineers have traditionally focused on how fast they could drive a chemical reaction. In such situations, however, catalysts often drive more than one reaction, yielding unwanted byproducts that have to be separated out. Also, traditional catalysts sometimes lose strength in the reaction process. Madey says that these problems could be minimized by tailoring nanostructured metal surfaces on supported industrial catalysts, making new forms of catalysts that are more robust and selective.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.