A Boost for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Research

Advertisement

The development of hydrogen fuel cells for vehicles is another step closer. Researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) have identified a new variation of a familiar platinum-nickel alloy that is the most active oxygen-reducing catalyst ever reported.

The slow rate of oxygen-reduction catalysis on the cathode - a fuel cell's positively charged electrode - has been a primary factor hindering development of the polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) fuel cells favored for use in vehicles powered by hydrogen.

"The existing limitations facing PEM fuel cell technology applications in the transportation sector could be eliminated with the development of stable cathode catalysts with several orders of magnitude increase in activity over today's state-of-the-art catalysts, and that is what our discovery has the potential to provide," said Vojislav Stamenkovic, a scientist with dual appointments in the Materials Sciences Division of both Berkeley Lab and Argonne.

Stamenkovic and Argonne senior scientist Nenad Markovic are the corresponding authors of a study whose results are now available online from the journal Science. The paper, entitled Improved Oxygen Reduction Activity on Pt3Ni(111) via Increased Surface Site Availability, reports a platinum-nickel alloy that increased the catalytic activity of a fuel cell cathode by an astonishing 90-fold over the platinum-carbon cathode catalysts used today.

"Massive application of PEM fuel cells as the basis for a renewable hydrogen-based energy economy is a leading concept for meeting global energy needs," said Stamenkovic. "Since the only byproduct of PEM fuel cell exploitation is water vapor, their widespread use should have a tremendously beneficial impact on greenhouse gas emissions and global warming."

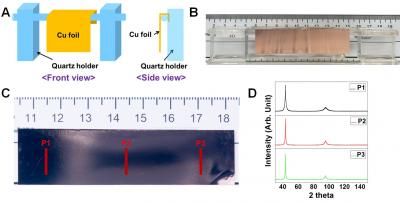

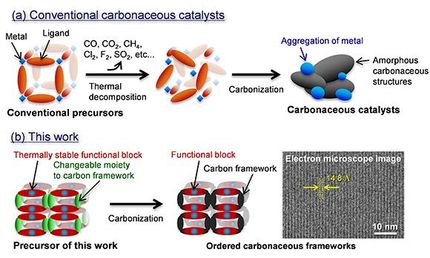

A challenge has been the platinum. While pure platinum is an exceptionally active catalyst, it is quite expensive and its performance can quickly degrade through the creation of unwanted by-products, such as hydroxide ions. Hydroxides have an affinity for binding with platinum atoms and when they do this they take those platinum atoms out of the catalytic game. As this platinum-binding continues, the catalytic ability of the cathode erodes. Consequently, researchers have been investigating the use of platinum alloys in combination with a surface enrichment technique. Under this scenario, the surface of the cathode is covered with a "skin" of platinum atoms, and beneath are layers of atoms made from a combination of platinum and a non-precious metal, such as nickel or cobalt. The subsurface alloy interacts with the skin in a way that enhances the overall performance of the cathode. For this latest study, Stamenkovic and Markovic and their colleagues created pure single crystals of platinum-nickel alloys across a range of atomic lattice structures in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber. They then used a combination of surface-sensitive probes and electrochemical techniques to measure the respective abilities of these crystals to perform ORR catalysis. The ORR activity of each sample was then compared to that of platinum single crystals and platinum-carbon catalysts.

The researchers identified the platinum-nickel alloy configuration Pt3Ni(111) as displaying the highest ORR activity that has ever been detected on a cathode catalyst - 10 times better than a single crystal surface of pure platinum(111), and 90 times better than platinum-carbon. In this (111) configuration, the surface skin is a layer of tightly packed platinum atoms that sits on top of a layer made up of equal numbers of platinum and nickel atoms. All of the layers underneath those top two layers consist of three atoms of platinum for every atom of nickel.

According to Stamenkovic, the Pt3Ni(111) configuration acts as a buffer against hydroxide and other platinum-binding molecules, blunting their interactions with the cathode surface and allowing for far more ORR activity. The reduced platinum-binding also cuts down on the degradation of the cathode surface.

The next step, Stamenkovic said, will be to engineer nanoparticle catalysts with electronic and morphological properties that mimic the surfaces of pure single crystals of Pt3Ni(111).