To use all functions of this page, please activate cookies in your browser.

my.chemeurope.com

With an accout for my.chemeurope.com you can always see everything at a glance – and you can configure your own website and individual newsletter.

- My watch list

- My saved searches

- My saved topics

- My newsletter

PolaronPolaron is a quasiparticle composed of an electron plus its accompanying polarization field. A slow moving electron in a dielectric crystal, interacting with lattice ions through long-range forces will permanently be surrounded by a region of lattice polarization and deformation caused by the moving electron. Moving through the crystal, the electron carries the lattice distortion with it, thus one may speak of a cloud of phonons accompanying the electron. The resulting lattice polarization acts as a potential well that hinders the movements of the charge, thus decreasing its mobility. Polarons have spin, though two close-by polarons are spinless. The latter is called a bipolaron. In materials science, a polaron is formed when a charge within a molecular chain influences the local nuclear geometry, causing an attenuation (or even reversal) of nearby bond alternation amplitudes. This "excited state" possesses an energy level between the lower and upper bands. The concept of a polaron is used while discussing ways for making a polymer electrically conductive. As an example, PPV (poly paraphenylenevinylene), is presently the most popular commercially available conducting polymer. In this it is tried to create an excited state which is then eventually relaxed and the energy is emitted either in a radiative manner (emitting light) or a non radiative manner (vibration etc). One of the simplest ways to create such an "excited state" (i.e. a polaron) is by alternating the bond geometry which is done by doping the polymer. In a bipolaron two charged units exist within a molecular chain. A polaron liquid has been found in doped cuprate perovskites showing high Tc superconductivity. Product highlight

Polaron theoryL. D. Landau [1] and S. I. Pekar [2] were at the basis of polaron theory. A charge placed in a polarizable medium will be screened. Dielectric theory describes the phenomenon by the induction of a polarization around the charge carrier. The induced polarization will follow the charge carrier when it is moving through the medium. The carrier together with the induced polarization is considered as one entity, which is called a polaron (see Fig. 1).

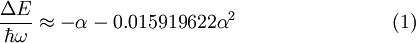

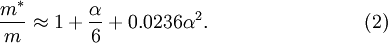

The polarization, carried by the longitudinal optical (LO) phonons, is represented by a set of quantum oscillators with frequency ω, the long-wavelength LO-phonon frequency, and the interaction between the charge and the polarization field is linear in the field. This model (which up to now has not been solved exactly) has been the subject of extensive investigations [2][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]. The strength of the electron-phonon interaction is expressed by a dimensionless coupling constant α introduced by Fröhlich [6]. In Table 1 the Fröhlich coupling constant is given for a few solids. The physical properties of a polaron differ from those of a band-carrier. A polaron is characterized by its self-energy ΔE, an effective mass m * and by its characteristic response to external electric and magnetic fields (e. g. dc mobility and optical absorption coefficient). When the coupling is weak (α small), the self-energy of the polaron can be approximated as [12]:

and the polaron mass m * , which can be measured by cyclotron resonance experiments, is larger than the band mass m of the charge carrier without self-induced polarization [13]:

When the coupling is strong (α large), a variational approach due to Landau and Pekar indicates that the self-energy is proportional to α² and the polaron mass scales as α⁴. Feynman [14] introduced a variational principle for path integrals to study the polaron. He simulated the interaction between the electron and the polarization modes by a harmonic interaction between a hypothetical particle and the electron. The analysis of an exactly solvable ("symmetrical") 1D-polaron model [15][16], Monte Carlo schemes [17][18] and other numerical schemes [19] demonstrate the remarkable accuracy of Feynman's path-integral approach to the polaron ground-state energy. Experimentally more directly accessible properties of the polaron, such as its mobility and optical absorption, have been investigated subsequently. Polaron optical absorptionThe expression for the magnetooptical absorption of a polaron is [20]:

Here, ωc is the cyclotron frequency for a rigid-band electron. The magnetooptical absorption Γ(Ω) at the frequency Ω takes the form Σ(Ω) is the so-called "memory function", which describes the dynamics of the polaron. Σ(Ω) depends also on α, β and ωc. In the absence of an external magnetic field (ωc = 0) the optical absorption spectrum (3) of the polaron at weak coupling is determined by the absorption of radiation energy, which is reemitted in the form of LO phonons. At larger coupling,

A comparison of the DSG results [21] with the optical conductivity spectra given by approximation-free numerical [22] and approximate analytical approaches is given in ref. [23]. Calculations of the optical conductivity for the Fröhlich polaron performed within the Diagrammatic Quantum Monte Carlo method [22], see Fig. 3, fully confirm the results of the path-integral variational approach [21] at

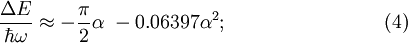

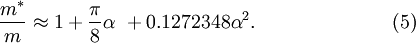

The application of a sufficiently strong external magnetic field allows one to satisfy the resonance condition Ω = ωc + ReΣ(Ω), which {(for ωc < ω)} determines the polaron cyclotron resonance frequency. From this condition also the polaron cyclotron mass can be derived. Using the most accurate theoretical polaron models to evaluate Σ(Ω), the experimental cyclotron data can be well accounted for. Evidence for the polaron character of charge carriers in AgBr and AgCl was obtained through high-precision cyclotron resonance experiments in external magnetic fields up to 16 T [25]. The all-coupling magneto-absorption calculated in ref. [26], leads to the best quantitative agreement between theory and experiment for AgBr and AgCl. This quantitative interpretation of the cyclotron resonance experiment in AgBr and AgCl [25] by the theory of ref. [26] provided one of the most convincing and clearest demonstrations of Fröhlich polaron features in solids. Experimental data on the magnetopolaron effect, obtained using far-infrared photoconductivity techniques, have been applied to study the energy spectrum of shallow donors in polar semiconductor layers of CdTe [27]. The polaron effect well above the LO phonon energy was studied through cyclotron resonance measurements, e. g., in II-VI semiconductors, observed in ultra-high magnetic fields [28]. The resonant polaron effect manifests itself when the cyclotron frequency approaches the LO phonon energy in sufficiently high magnetic fields. Polarons in two dimensions and in quasi-2D structuresThe great interest in the study of the two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) has also resulted in many investigations on the properties of polarons in two dimensions [29][30][31]. A simple model for the 2D polaron system consists of an electron confined to a plane, interacting via the Fröhlich interaction with the LO phonons of a 3D surrounding medium. The self-energy and the mass of such a 2D polaron are no longer described by the expressions valid in 3D; for weak coupling they can be approximated as [32][33]:

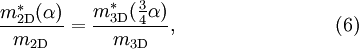

It has been shown that simple scaling relations exist, connecting the physical properties of polarons in 2D with those in 3D. An example of such a scaling relation is [31]:

where The effect of the confinement of a Fröhlich polaron is to enhance the effective polaron coupling. However, many-particle effects tend to counterbalance this effect because of screening [29]. Also in 2D systems cyclotron resonance is a convenient tool to study polaron effects. Although several other effects have to be taken into account (nonparabolicity of the electron bands, many-body effects, the nature of the confining potential, etc.), the polaron effect is clearly revealed in the cyclotron mass. An interesting 2D system consists of electrons on films of liquid He [34][35]. In this system the electrons couple to the ripplons of the liquid He, forming "ripplopolarons". The effective coupling can be relatively large and, for some values of the parameters, self-trapping can result. The acoustic nature of the ripplon dispersion at long wavelengths is a key aspect of the trapping. For GaAs/AlxGa1-xAs quantum wells and superlattices, the polaron effect is found to decrease the energy of the shallow donor states at low magnetic fields and leads to a resonant splitting of the energies at high magnetic fields. The energy spectra of such polaronic systems as shallow donors ("bound polarons"), e. g., the D0 and D- centres, constitute the most complete and detailed polaron spectroscopy realised in the literature [36]. In GaAs/AlAs quantum wells with sufficiently high electron density, anticrossing of the cyclotron-resonance spectra has been observed near the GaAs transverse optical (TO) phonon frequency rather than near the GaAs LO-phonon frequency [37]. This anticrossing near the TO-phonon frequency was explained in the framework of the polaron theory [37]. Besides optical properties [10][4][38], many other physical properties of polarons have been studied, including the possibility of self-trapping, polaron transport [39], magnetophonon resonance, etc. Extensions of the polaron conceptSignificant are also the extensions of the polaron concept: acoustic polaron, piezoelectric polaron, electronic polaron, bound polaron, trapped polaron, spin polaron, molecular polaron, solvated polarons, polaronic exciton, Jahn-Teller polaron, small polaron, bipolarons and many-polaron systems [4]. These extensions of the concept are invoked, e. g., to study the properties of conjugated polymers, colossal magnetoresistance perovskites, high-Tc superconductors, layered MgB2 superconductors, fullerenes, quasi-1D conductors, semiconductor nanostructures. The possibility that polarons and bipolarons play a role in high-Tc superconductors has renewed interest in the physical properties of many-polaron systems and, in particular, in their optical properties. Theoretical treatments have been extended from one-polaron to many-polaron systems [4][40]. A new aspect of the polaron concept has been investigated for semiconductor nanostructures: the exciton-phonon states are not factorizable into an adiabatic product Ansatz, so that a non-adiabatic treatment is needed [41]. The non-adiabaticity of the exciton-phonon systems leads to a strong enhancement of the phonon-assisted transition probabilities (as compared to those treated adiabatically) and to multiphonon optical spectra that are considerably different from the Franck-Condon progression even for small values of the electron-phonon coupling constant as is the case for typical semiconductor nanostructures [41]. In biophysics Davydov soliton is a propagating along the protein α-helix self-trapped amide I excitation that is a solution of the Davydov Hamiltonian. The mathematical techniques that are used to analyze Davydov's soliton are similar to some that have been developed in polaron theory. In this context the Davydov soliton corresponds to a polaron that is (i) large so the continuum limit approximation in justified, (ii) acoustic because the self-localization arises from interactions with acoustic modes of the lattice, and (iii) weakly coupled because the anharmonic energy is small compared with the phonon bandwidth [42]. References and notes

Categories: Condensed matter physics | Ions |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Polaron". A list of authors is available in Wikipedia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\Gamma(\Omega) \propto -\frac{\mathrm{Im} \Sigma(\Omega)}{\left[\Omega-\omega_{\mathrm{c}}-\mathrm{Re} \Sigma(\Omega)\right]^2 + \left[\mathrm{Im}\Sigma(\Omega)\right]^2} . \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (3)](images/math/2/7/1/2714bdfb820740792c64a977232b850a.png)

, the polaron can undergo transitions toward a relatively stable internal excited state called the "relaxed excited state" (RES) (see Fig. 2). The RES peak in the spectrum also has a phonon sideband, which is related to a Franck-Condon-type transition.

, the polaron can undergo transitions toward a relatively stable internal excited state called the "relaxed excited state" (RES) (see Fig. 2). The RES peak in the spectrum also has a phonon sideband, which is related to a Franck-Condon-type transition.

In the intermediate coupling regime

In the intermediate coupling regime

(

( ) and

) and  (

( ) are, respectively, the polaron and the electron-band masses in 2D (3D).

) are, respectively, the polaron and the electron-band masses in 2D (3D).