Charging ahead: University of Houston team revealing secrets of electricity-producing materials

Researchers press on in their mission to power nanodevices of tomorrow

Advertisement

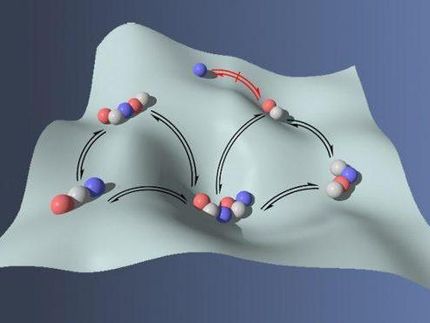

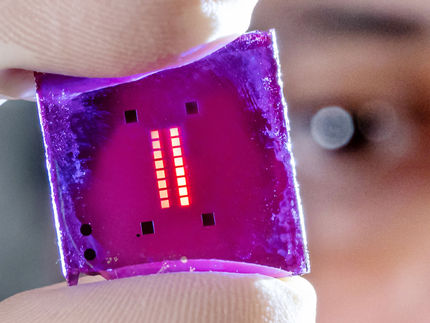

Much like humans, materials are capable of some pretty remarkable things when they're placed under pressure. In fact, under the right conditions, materials can even produce electricity. Driven by the vision of our society one day being basically self-propelled, a team of University of Houston scientists has set out to both amplify and provoke that potential in materials known as piezoelectrics, which naturally produce electricity when literally subjected to strain. The goal is to use piezoelectrics to create nanodevices that can power electronics, such as cell phones, MP3 players and even biomedical implants.

Although piezoelectrics have been used for many years, associate professor Pradeep Sharma's team is exploring new possibilities by beefing up the effect in natural piezoelectrics. Doing so requires understanding the phenomenon that spurs piezoelectricity, known as "flexoelectricity."

"Flexoelectricity, at the nanoscale, allows you to coax ordinary material to behave like a piezoelectric one. Perhaps more importantly, this phenomenon exists in materials that are already piezoelectric. You can make the effect even larger," Sharma says.

For example, the piezoelectricity in barium titanate can be increased by 300 percent when the material is reduced to a 2-nanometer-beam and pressure is applied. "Thus, you'll take an ordinary piezoelectric material and really give it some juice," he says.

Sharma underscores the flexoelectric effect is a function of size – and the smaller the better, at least for generating piezoelectric power. Materials with nanoscale features – such as nanoscale thin plates stacked on each other or materials with particles or holes the size of a few nanometers – exhibit a much larger flexoelectric effect, he says.

Ramanan Krishnamoorti, chairman of the department of chemical and biomolecular engineering, is working with Sharma to embed classes of nanostructures in polymers to create unusual types of piezoelectrics. Meanwhile, Sharma and professor Ken White recently reported that the electrical activity caused by flexoelectricity also affects a material's resiliency. They tested their theory – that the elasticity of a material would be quite altered by flexoelectricity-caused electrical activity – by poking the material with a sophisticated needle.

"We basically predicted that when you poke it, because of this electrical activity, depending upon how big a crater you create, your elastic behavior will change. It's not supposed to. Ordinarily, whether you make a big crater or small crater, if you calculate how stiff it is or soft it is, it'll give you the same answer – a constant," Sharma says.

Though a fair amount of research on piezoelectrics has been done, White says, the fabrication of piezoelectric nanostructures remains challenging. The amount of power that can be harvested is still too low to actually power wearable devices, he says, unless efficient electric storage solutions, like nanocapacitors, also are conceived.