Production of solar fuels inches closer with news discovery

Advertisement

Caltech researchers have made a discovery that they say could lead to the economically viable production of solar fuels in the next few years.

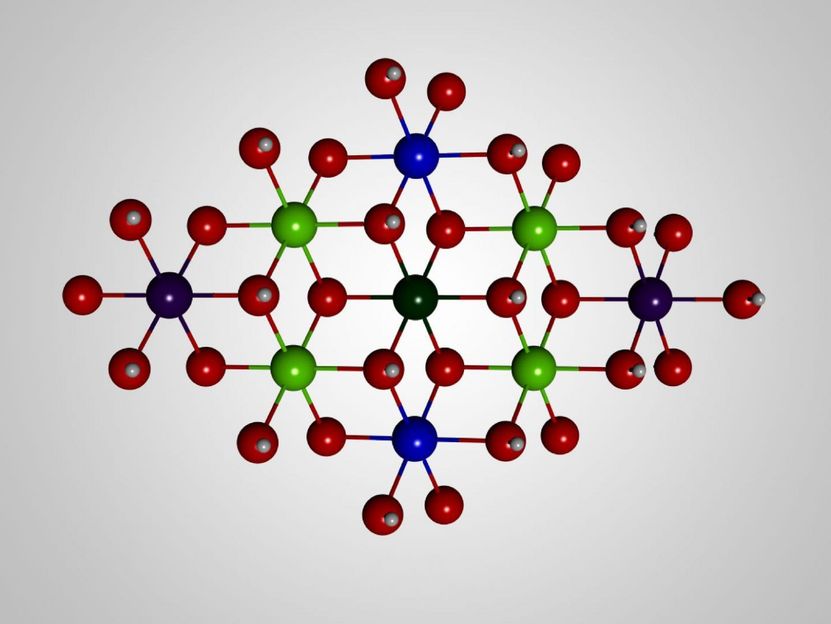

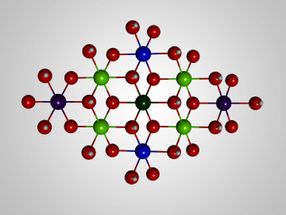

This is a ball-and-stick model of the molecular structure of the solar-fuel catalyst developed at Caltech. Blue represents iron atoms; green is nickel; red is oxygen; white is hydrogen.

Caltech

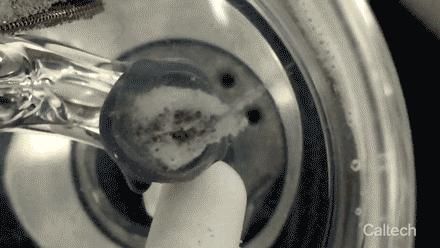

This is gas generation by a solar-fuel catalyst.

Caltech

For years, solar-fuel research has focused on developing catalysts that can split water into hydrogen and oxygen using only sunlight. The resulting hydrogen fuel could be used to power motor vehicles, electrical plants, and fuel cells. Since the only thing produced by burning hydrogen is water, no carbon pollution is added to the atmosphere.

In 2014, researchers in the lab of Harry Gray, Caltech's Arnold O. Beckman Professor of Chemistry, developed a water-splitting catalyst made of layers of nickel and iron. However, no one was entirely sure how it worked. Many researchers hypothesized that the nickel layers, and not the iron atoms, were responsible for the water-splitting ability of the catalyst (and others like it).

To find out for sure, Bryan Hunter (PhD '17), a former fellow at the Resnick Institute, and his colleagues in Gray's lab created an experimental setup that starved the catalyst of water. "When you take away some of the water, the reaction slows down, and you are able to take a picture of what's happening during the reaction," he says.

Those pictures revealed the active site of the catalyst--the specific location where water is broken down into oxygen--and showed that iron was performing the water-splitting reaction, not nickel.

"Our experimentally supported mechanism is very different than what was proposed," says Hunter describing the discovery. "Now we can start making changes to this material to improve it."

Gray, whose work has focused on solar fuels for decades, says the discovery could be a "game changer" for the field.

"This will alert people worldwide that iron is particularly good for this kind of catalysis," he says. "I wouldn't be at all shocked if people start using these catalysts in commercial applications in four or five years."